You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Superior Court for the County of Los Angeles | Getty Images

Who gets to claim alumni status at the University of Southern California and benefit from its powerful network?

For years, Brian Ralston, who earned a graduate certificate in music scoring for motion pictures and television from USC in 2002, thought he did.

After all, he’d attended a commencement ceremony wearing a hooded gown and cap just like the graduates of traditional master’s programs, and the university referred to his and other graduate certificate programs as a “degree” on its website. That “conferred degree from USC” was the only requirement for membership in the alumni association, according to an archived webpage from the early 2000s.

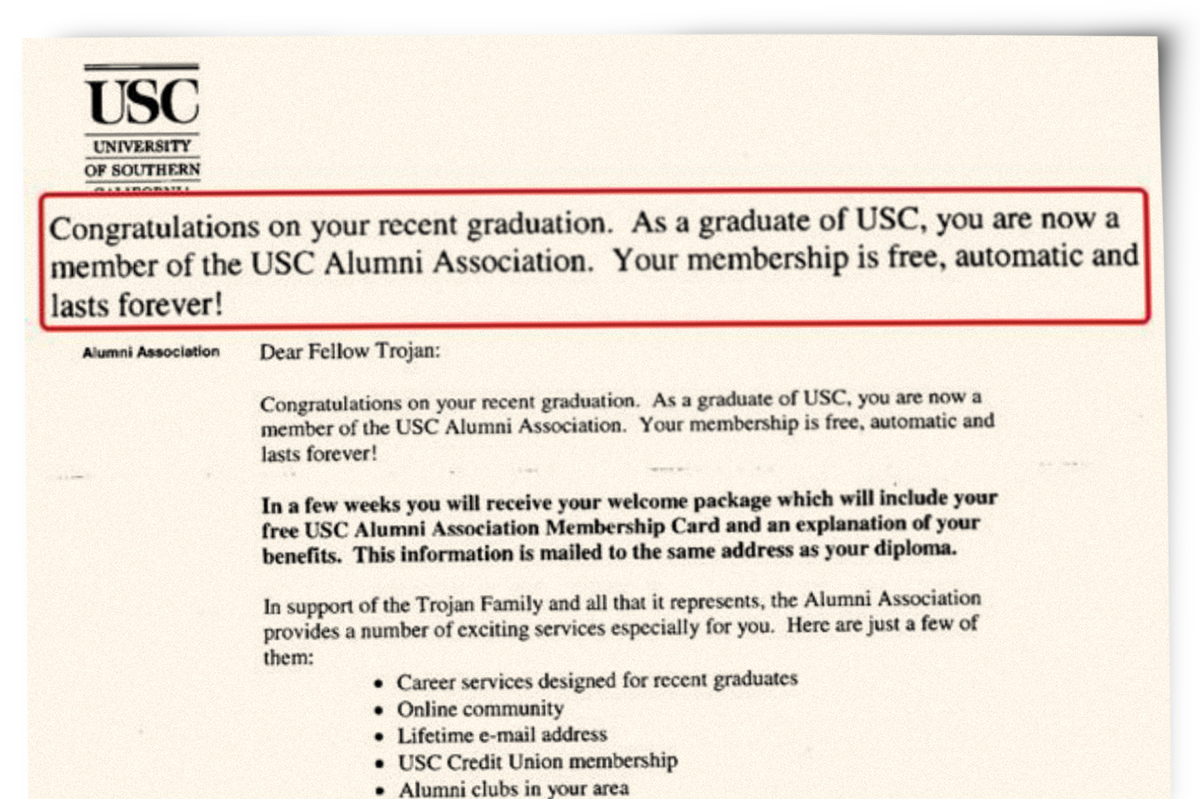

And soon after graduating, Ralston received a letter from the alumni association’s associate vice president informing him that, as a graduate of USC, “you are now a member of the USC Alumni Association. Your membership is free, automatic and lasts forever!”

The membership, which Ralston had access to for many years, comes with numerous perks, including access to an exclusive online alumni directory containing contact information—searchable by name, degree, location, employment and involvement—for all USC alumni. It also gives graduates access to an online message board, where alumni post job and business opportunities, and a 10 percent discount at the campus bookstore, which sells pricey electronics.

Superior Court for the County of Los Angeles

But in 2021, Ralston, who writes music for film and television, was talking to a colleague who graduated from the same certificate program and had tried, unsuccessfully, to use the alumni discount. They learned the university had updated its bylaws sometime in the 2010s—without notifying affected graduates—to no longer grant alumni status to graduate certificate holders who don’t otherwise have a traditional bachelor’s or graduate degree from USC.

“As such,” graduate certificate holders “are not entitled to various alumni benefits,” said Patrick E. Auerbach, USC’s associate senior vice president of alumni relations, in an email.

“It was quite a shock,” Ralston said. “It felt like there was a promise and commitment made that they did not hold up.”

Ralston and his colleague were not the only ones whose alumni status was canceled without notice. Some 1,631 graduates of USC’s various certificate programs who graduated between 2000 and 2022 (and did not otherwise hold a traditional bachelor’s or graduate degree) also lost alumni status.

Ralston and the other affected graduates sent “a pre-suit demand letter” to USC on Feb. 23, 2022, “hoping to resolve this matter without litigation,” but USC did not restore their alumni status and benefits, according to the lawsuit.

The certificate holders filed a class action lawsuit against the USC Alumni Association and the university last year.

The dispute at USC comes at a time when certificate programs are ascendant at many colleges and universities—and one of the few areas of growth at a time of shrinking enrollment over all. The situation raises issues of whether colleges value some students and credentials less than others, even when those learners are paying tens of thousands of dollars for their educational experiences.

‘Have Its Cake and Eat It, Too’?

The complaint accuses USC and its alumni association of long-term false advertising and provides numerous pieces of evidence showing how the university “represented and advertised” that a graduate certificate “degree would include automatic lifetime membership in the USC Alumni Association with access to all Alumni Benefits.”

Those purported lifelong alumni benefits were major factors in Ralston’s decision to enroll in the certificate program back in 2001. He spent $26,356 on the one-year, full-time program, according to the complaint.

“A lot of people in the industry have gatekeepers,” Ralston said in an interview. But the USC alumni directory offers “more direct ways of communicating” with other USC graduates who have already found their footing in a particular field. “Being able to research potential collaborators and filmmakers who went to USC, especially during the times I went there, can be beneficial.”

Figure 16 from the lawsuit shows a letter from the University of Southern California welcoming recent graduates into the USC Alumni Association, which is "free, automatic and lasts forever."

Superior Court for the County of Los Angeles

Ralston’s lawyers spent the past year negotiating a settlement with USC, and last week, Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Carolyn B. Kuhl accepted a filing for a settlement. A motion for preliminary approval of the proposed settlement is set for hearing on Oct. 11.

A USC spokesperson did not provide direct answers to questions about when and why the alumni association rescinded the memberships and instead pointed to the terms of the settlement, which is subject to court approval.

If the judge grants preliminary approval in October, Ralston and his co-plaintiffs would get their membership in the alumni association reinstated, and USC and its alumni association would have to pay up to $165,000 of the plaintiffs’ legal fees. The plaintiffs would also get a $50 coupon to the bookstore, which is enough to cover the price of a crewneck sweatshirt before taxes.

USC would also be required to correct its advertising to make clear what kind of benefits graduates of certificate programs can expect to receive, including whether they will become members of the alumni association upon graduation.

The university did not make clear if it intends to offer future graduate certificate holders alumni status.

Lizelle Brandt, the lead attorney representing Ralston and his co-plaintiffs, said she didn’t seek a higher-dollar settlement amount because “it was tough to quantify” the financial losses of losing alumni status.

She said one of the real values of settling this case is correcting USC’s attempt to “have its cake and eat it, too.”

The complaint details how USC stripped certificate program graduates of their alumni status while publicly claiming well-known certificate graduates—such as Ludwig Göransson, who won an Oscar for composing the score for the film Black Panther—as “alumni” online.

If USC’s graduate certificates “are going to be considered lesser programs because they want their alumni association to be exclusive, then why don’t they just create a USC extension?” Brandt said. She referred to the complaint’s comparison that both Harvard and the University of California, Los Angeles, grant certificates through extension schools and clearly indicate if graduates of those programs can expect to claim full alumni status.

“We’re guessing” USC doesn’t “because they still want to be able to charge full tuition,” Brandt said. But if USC discloses “that these are lesser programs and you won’t be part of this alumni association and have access to those benefits, would people still pay that same tuition instead of going to another certificate program somewhere else?”

According to the complaint, USC charged students enrolled in the scoring for motion pictures and television graduate certificate program (it has since been converted into a full-fledged master’s program) $49,464 for one year during the 2015–16 academic year. Full tuition that year for traditional undergraduate and graduate students was $49,464.

‘Messy Environment’

Certificate programs have been around for decades, but they have “become much more popular in terms of university offerings and student demand, and those two things are responding to each other,” said Sean R. Gallagher, a professor of educational policy at Northeastern University. “They’ve also become much more accessible due to the rise of online options over the last 25 years and especially the last 10 years.”

While there is some debate about their value, he noted that “the data seems to indicate that employers seem to very much value workers with higher education and people who have pursued graduate-level education or education beyond a bachelor’s.”

As many colleges and universities across the country grapple with a slide in overall enrollment, certificate programs are showing the strongest growth of any higher education sector, according to spring 2023 data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

But even as they gain popularity with students, the wide variation in selectivity, costs and services associated with certificate programs has created a “messy environment,” Gallagher said. “It’s really important for students to understand what they’re going to have access to … and that includes alumni networks.”

Lauren Rivera, a professor of management and organizations at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management whose research focuses on prestige in higher education, said, “For better or worse, many people look at the prestige of the school you attend as a reflection of your worth as a potential employee or member of society.”

As a result, universities “have a vested interest in preserving perceptions of their own status,” she said. Alumni groups, which are proven to boost entry into the job market, “also want to preserve their status to be able to convey to the world that they’re a rarefied group of people who are highly selected.”

And since “the notion of status is predicated on exclusion,” Rivera said, “it makes sense that USC would want to preserve the signaling power of their credential by, in some respects, gatekeeping who they do and don’t affiliate with.”