You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The UT Creamery reopened on the Knoxville campus last August, offering experiential learning opportunities for students and a new hangout spot for students, alumni and visitors.

UT Knoxville

It’s a hot and sticky August afternoon in Knoxville as University of Tennessee students push their way through the doors of the newly opened UT Creamery, welcomed by their peers working behind the counters at the retro-themed ice cream parlor.

On the parlor’s opening weekend, UT Creamery staff served five flavors—VOLnilla, Torchbearer’s Chocolate, Smokey’s Strawberry Kisses, Mint Champion Chip and Go Big Orange—which had the fingerprints of dozens of college students, from workers at the dairy farm on campus to those in ice cream production labs and product development and, finally, student workers scooping the sweet treats to serve to customers.

This fall, UT Knoxville rejoined a small cohort of other land-grant universities selling dairy products developed by students on campus. College creameries are a multipronged approach to student experiential learning, involving student research and entrepreneurship in long-standing university traditions.

At a Glance

College creameries add value to an institution by:

- Providing on-campus work for student employees

- Creating experiential learning opportunities for food science and marketing students

- Establishing a space for socialization and campus engagement

- Educating the general public and local farmers on best practices in product development

- Continuing institutional history and tradition

A Rebirth of College Creameries

The first college creameries appeared in the late 19th century, tied in part to Congress’s 1862 Morrill Act, which established the agriculture-based public land-grant institutions. Many land-grant universities, particularly in the Midwest and Southern U.S., had an on-campus dairy, providing fresh milk and other dairy products to students for retail sale or in the dining facilities.

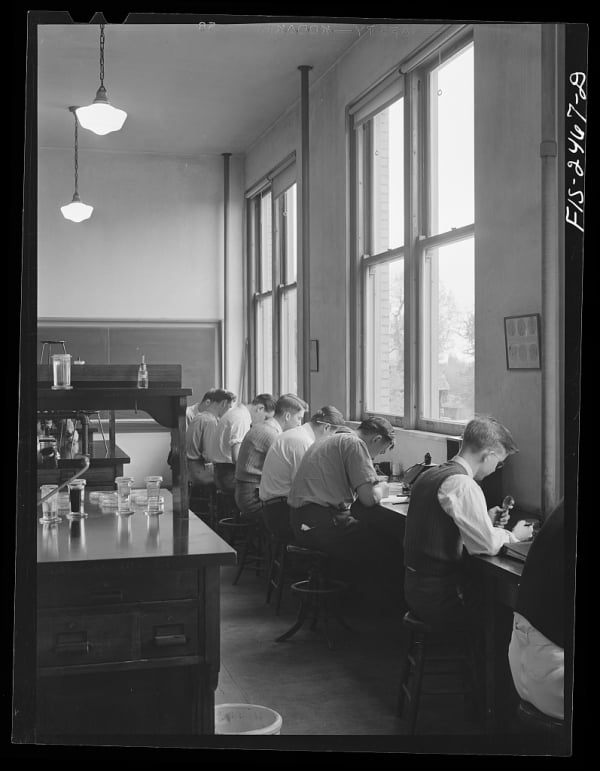

Students milk cows at Iowa State University’s dairy in 1942. The Iowa State farm, according to the Library of Congress archives, was used for both classroom work and research, and some students worked at the dairy to pay their way through school.

Jack Delano/Library of Congress

Pennsylvania State University is home to one of the country’s oldest university creameries—established in 1865—and it is now the largest college creamery in the U.S. The Berkey Creamery uses around 4.5 million pounds of milk each year, producing more than 150 ice cream flavors that are distributed around the country and the globe.

While ice cream is one of the most common products from college creameries, cheese is also a lucrative product. Washington State University’s creamery is known for its Cougar Gold cheese, which, along with ice cream, brings the university about a quarter of a million dollars in revenue each year.

During the 1980s, many college dairies (including UT’s) closed their doors due to economic hardship. “Dramatic changes in the dairy processing industry heightened challenges for small-scale dairy businesses,” Iowa State University’s creamery history says.

More recently, there’s been a resurrection of college creameries thanks to donors and outside partners, with around 20 now in operation. The University of Missouri’s Buck’s Ice Cream restarted in 1989 with an endowment from two Mizzou alumni.

“They wanted ice cream back on campus,” explains Rick Linhardt, who managed the operation for many years.

Clemson University also received a gift from alumni to renew the campus creamery, as did UT. Middle Tennessee State University’s creamery jolted back to life in 2017 after a 50-year hiatus, as did Iowa State’s in 2020.

Milking the Experience

The value of a college creamery, beyond providing delicious dairy products to hungry students, is the training opportunities it provides. Washington State University creamery manager John Francis Haugen jokes that the main export is not cheese, but students.

“We’ve really turned the focus from just producing milk, like they used to, to students getting practical work experience as part of their education here,” Haugen says.

Small creameries—like Mizzou’s, which makes around 313 gallons of ice cream each month—allow students to have a greater role in the product life cycle because there are no full-time staff members, beyond supervisors. WSU’s creamery is run by about 60 to 70 students each term, adding additional employees during the holiday season to meet demand.

Student employees at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville learn customer service and management skills, as well as how to run a creamery.

UT Knoxville

“The students learn every aspect of the process, from start to finish,” Mizzou’s Lindhardt says, from equipment assembly to prep work and sanitation to flavor research and retail work.

UT’s creamery is a partnership between the Herbert College of Agriculture; the Department of Retail, Hospitality and Tourism Management (RHTM); and the College of Education, Health and Human Sciences. Student roles are divided into three primary categories: food and product production, marketing and communications, and operational roles within the creamery.

“It’s like a three-prong of student experiential learning,” says Myra Loveday, director of the UT Creamery.

Food science students learn the chemistry of ice cream and how to produce products, experimenting with ingredients and flavors to mix up delicious flavors.

RTIR students conduct market research, identifying what flavors students are interested in and creating unique flavor names and descriptions. Each UT flavor ties back to the university’s history and traditions—the coffee-flavored ice cream Midnight at Hodges hints at students’ late-night study habits in the on-campus library, and the birthday cake flavor, 1794, pays homage to the founding year of UT.

Survey Says

A 2023 Student Voice survey from Inside Higher Ed and College Pulse found 40 percent of students believe developing specific skills needed for their careers is among the most important outcomes in their academic experiences.

Over half of students believe internships should be included or required in their academic programs, followed by fieldwork (36 percent), clinical experiences (28 percent) and undergraduate research (27 percent).

Additionally, RTIR students designed the ice cream parlor, putting together menu displays, picking out furniture and creating operational processes.

Finally, student employees from a variety of majors on campus serve as the face of UT Creamery in the retail business, engaging with customers, developing customer-relations skills and conducting store operations. Student employees at the UT Creamery earn $15 per hour, running the facility Monday to Saturday, noon to 7 p.m., Loveday says.

“Even though they may be [in] anthropology or nursing or other fields of study, they get to see different pieces of how our retail business works,” Loveday says. “That is just a big plus in whatever career they go into—they’re going to have to understand customer service and working with people who think differently.”

Dairy Education

Beyond creating products for sale at the university locations, campus creameries provide space for faculty-led or graduate research through dairy extension programs.

“When I was trained, it was drilled into me that for the creamery to be part of the university, we needed to not just be making all the cheese we can and selling it. If we’re going to do that, we’d hire full-time people and not use college students,” Fr WSU’s Haugen says. “So we need to make sure that in what we’re doing, there’s teaching, research and extension-type activities involved.”

The UT Creamery gives food science students an avenue to develop dairy products.

UT Knoxville

WSU has a pilot plant available for outside partners or graduate students to use for research that also offers the Cheesemaking Shortcourse and a pasteurization workshop for community members to learn more about dairy production.

Identifying low-fat or allergen-free alternatives is a newer element of ice cream research. Mizzou researchers are currently experimenting with a soybean oil also produced at the university to create a dairy-free frozen dessert alternative, shares Bongkosh Vardhanabhuti, associate professor of food science. UT is considering its own nondairy alternative, an orange sherbet.

Jack Delano/Library of Congress

Some students get involved in the creamery as part of for-credit classes. Mizzou offers experiential learning labs for wine and meat products in addition to dairy. This term, 15 students enrolled in the food product development class are working in small groups to develop new ice cream flavors, says Andrew Clarke, associate professor of food science.

UT is considering adding educational components to its facility, helping local dairy farmers create more profitable offerings, says David White, interim dean of the Herbert College of Agriculture. “The dairy industry is slowly dying … so if we can help farmers with value-added ideas and show that we can make it work, they can pivot to make money and survive.”

A Taste of Success

Not every student who’s involved in the creamery is looking to get a head start in the dairy industry, but students in any major can learn something from working at the creamery, Haugen says. “Some of the students, it’s their first job they’ve ever had, so learning how to show up on time and work with other human beings in a formal work environment is a benefit in itself.”

UT’s partnership between the various campus divisions allows students from different majors to collaborate in creating ice cream products. “I tell my students all the time, you do your expertise and let the other people do their expertise,” Loveday says. “That’s why we can come together and highlight each other’s field of study and also what they’re best at.”

Some student employees go on to work in ice cream or dairy, university leaders say. Mizzou alums have worked for Unilever and Breyer and Haugen remembers a computer science student landing a job at Leprino Cheese thanks to his role at the WSU Creamery.

A 2023 Student Voice survey from Inside Higher Ed and College Pulse found, among 3,000 undergraduate students, 43 percent believed experiential learning helped them realize they wanted a career in a given field.

Haugen himself is a WSU creamery alum; he worked as a student employee for three years while enrolled at the university and then at a manager level after graduating with an engineering degree.

“What makes it unique is the location. With it being in their college, [students] take ownership in a way that doesn’t really happen at other places,” says Stephen Evans, current manager of Buck’s Ice Cream at Mizzou. “I think it’s because they feel like it’s their spot and it’s something they’re proud to stand behind.”

Beyond helping students thrive in their work after graduating, campus creameries foster tradition and connection to the institution.

The WSU Creamery celebrated its 75th anniversary this year, and the renown of its products extends far beyond the Pullman community.

“If you’ve ever seen our cheese in a can, it’s very well recognized around the country,” Haugen says. “It’s surprising how many people, when they hear I work at the Creamery, know about Cougar Gold.”

Cougar Gold cheese, made and sold by students at Washington State University, is also distributed internationally, bringing in thousands of dollars of revenue for the university each year.

Washington State University

On-campus parlors are also a traditional stopping point for alumni and families visiting campus for a football game. “Ice cream is universal, and it brings people together,” Loveday says.

By reinstating its creamery, UT is recreating a piece of history. “We have people that are reaching out to us that used to work at the old creamery, and they have old memorabilia as well as old recipes for flavors,” says White, the agriculture dean. “There’s things we can experiment with and bring that back in the future.”

Seeking stories from campus leaders, faculty members and staff for our Student Success focus. Share here.

This article has been updated to correct the name of the College of Education, Health and Human Sciences and Retail, Hospitality and Tourism Management abbreviation.