You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Knowing there is no easy way to “fix transfer,” the Beyond Transfer Policy Advisory Board (PAB) seeks to tackle the complicated problems and hidden complexities associated with credit mobility and transfer. Financial disincentives—what they are, why they exist and how they impede progress on transfer and credit mobility—represent hidden complexities the PAB explores in its new paper released today.

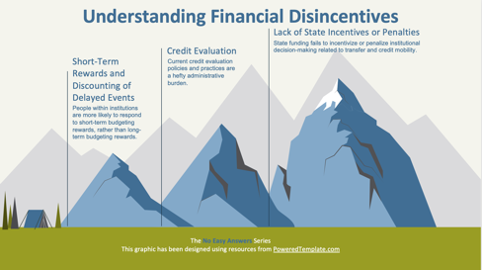

The financial disincentives that stymie equitable transfer flow from many sources, ranging from onerous credit evaluation practices to a lack of state funding models that incentivize or penalize institutional decision-making related to transfer and credit mobility (see Figure 1). For this blog, we focus on one of the most vexing reasons that financial disincentives persist: short-term thinking. Psychology explains that humans frequently make decisions guided by short-term rewards rather than long-term rewards, and they are likely to discount delayed events. Therefore, in the postsecondary education arena, institutional decision-makers respond to short-term budgeting rewards.

Figure 1

Postsecondary institutional budgets depend largely on tuition. Actors within postsecondary institutions—quite rationally—focus on the rewards of immediate student enrollment and the tuition revenues connected to that immediate enrollment over longer-term consequences. This can lead institutional actors to deny degree-applicable transfer credits in favor of increasing course-taking at the receiving institution, costing students time and money while reducing their likelihood of completing credentials. Examples of how this plays out can be complex and varied:

- Assumption of lost tuition: When receiving institutions conduct credit evaluation for students transferring to the institution, institutional actors may perceive credits accepted and applied as short-term financial disincentives, for the institution “gives up” the tuition it could have charged the student;

- Assumption of lower revenue margins: If institutional actors use only a short-term lens, they may conclude that students who transfer are more likely to take costly upper-division courses and create a lower revenue margin for the institution;

- Conflicting budgeting priorities within institutions: Imagine a student wishes to transfer to a university and apply credit for a previously-taken calculus course to progress on a pathway in the physics department. The math department may benefit by denying the credits and making the student retake calculus. Then, the math department can charge tuition for that course, report higher course-taking and assign faculty to more courses. That same decision may harm the physics department and the institution because the student may be less likely to persist and complete the physics degree; and

- Encouraging students to stay at a sending institution for as long as possible: Sending institutions may want to maintain enrollment and tuition revenue of each student. Students may be encouraged, in this process, to stay longer than necessary or even advisable at the sending institution while taking courses that will not apply to a degree once the student transfers.

Short-term thinking is so prevalent and instinctive to human nature that it must be balanced with intentional policies and practices to offset its influences in decision-making. Solutions should spur direct action that changes the understanding and discussion about consequences, brings delayed consequences closer in time, or changes immediate consequences. Our recommendations include:

- Shift from assumptions to data by calculating return on investment (ROI): Leverage the TransferBOOST Affordability Financial Tool—developed as a collaboration between the Institute for Higher Education Policy, HCM Strategists and rpK GROUP that was funded by the ECMC Foundation—to replace assumptions about lost tuition or lower revenue margins with data about projected student enrollment and tuition revenues. This tool can help institutions better understand the value of students who transfer and are mobile to the institutional bottom line;

- Interrogate short-term financial gains alongside long-term financial and other gains: For example, students who can transfer and apply more credits are more likely to persist and complete, which translates into students taking more courses over time and also into improving both sending and receiving institutions’ persistence and completion metrics;

- Build a strategy from within the president’s office that illuminates the value of students who transfer and are mobile: With an analysis of both financial returns and returns to mission in hand, institutional presidents should take the next step and build strategic plans focused on transfer and credit mobility that demonstrate the consistency of the plans with their institutions’ missions;

- Improve credit evaluation practices in ways that benefit both students and institutions: Current approaches to credit evaluation are a hefty administrative burden and represent a financial disincentive for institutions to recruit, accept, focus on and work well with students who transfer. We call for institutions to interrogate current approaches and identify new practices and technology solutions that can reduce the administrative burden while improving results for students; and

- Change state funding to alter the financial incentives to which institutions respond: States have an important role to play. For example, ensure that institutions receive the same—or even more—funding for serving students who transfer and are mobile, require institutions to provide an evidence-based rationale when rejecting credits, and design financial consequences for noncompliance.

The Beyond Transfer PAB intends to deepen its work on financial disincentives. We welcome your ideas and suggestions. Join us on social media with #BeyondTransfer, and read the full paper and recommendations in Unpacking Financial Disincentives: Why and How They Stymie Degree-Applicable Credit Mobility and Equitable Transfer Outcomes.