You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

State disinvestment in public higher education might not be such a crisis after all, at least for the most vulnerable of students -- those who are from low-income backgrounds and who largely lack family help to pay for tuition.

The reason, according to a new study from New America, is that increases in federal aid spending from 1996 to 2012 fully offset declines in state and local government contributions for community college students and for independent students who attend four-year public institutions.

“There’s a perception that federal aid has not kept up with costs or prices, but that’s not the case,” said Jason Delisle, the report’s author and director of the Federal Education Budget Project at New America, a think tank based in Washington, D.C. “You’ve got a federal aid system that does a pretty good job of targeting low-income students.”

The Obama administration has increased spending on Pell Grants and college tax credits. And the White House used stimulus funds to shore up public college budgets as most states slashed funding during the recession.

Unlike many studies of government subsidies in higher education, the new paper uses a model devised by the U.S. Congressional Budget Office, including federal data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) about college financing at the student level.

As a result, the study is focused on how changes in financial aid affected what students and families paid for college during the 17-year period covered. It does not look at institutional behavior during those years, or the oft-debated question of whether increasing federal spending enabled tuition hikes -- the so-called Bennett Hypothesis.

In the paper, Delisle examined college sticker prices, meaning tuition and all living expenses -- including estimates of nontuition expenses for students who live at home. He then deducted all sources of aid to determine the amount students and families must finance out of pocket or with debt.

The study broke down the shares of those costs covered by students and families, state or local governments, colleges and the federal government. The federal side included grant aid, such as Pell Grants, as well as tax credits.

Federal loan amounts were considered to be covered by students and families, who have to pay off those balances. However, portions of federal loan amounts with terms better than the private market were included in the study's federal-subsidy bucket.

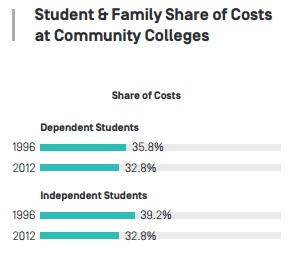

At community colleges, students and families paid a slightly smaller portion of college costs in 2012 than in 1996, a decline to 32.8 percent of costs from 35.8 percent. Likewise, independent students at public four-year institutions paid a smaller share of costs -- 37.4 percent compared to 41.6 percent.

“That finding contradicts the view that prices at public four-year colleges have risen significantly for all students,” the report said.

The study found a different story for dependent students, particularly wealthier ones.

For example, dependent students at four-year public institutions from families with annual household income of at least $106,000, the report’s highest income category, paid 64.8 percent of costs in 2012, a 3.3 percentage point increase from what they paid in 1996. In inflation-adjusted dollars, that was $3,045 more per year of education, or a total average amount of $18,350.

Students at private four-year colleges saw an increase in the share they and their families covered, across all income groups, the report found. But most of that increase occurred before 2004, with a slight decline in 2012.

However, students at private colleges who hail from the second-highest income group ($65,001 to $106,000) picked up more of the tab throughout the 17-year period.

“They get nailed,” said Delisle.

This group of students and their families paid 75.7 percent of college costs, compared to 66.3 percent in 1996, an increase of $5,719 in annual, inflation-adjusted costs, the biggest spike among all income groups and at any type of college the study tracked.

The report found that students and families relied heavily on debt to finance increases in their share of college costs, paying a smaller share out of pocket. That finding also extended to students who didn’t cover a larger portion of costs, such as those who attended community colleges.

Parent borrowing to pay for both public and private four-year colleges through federal PLUS loans increased significantly between 2008 and 2012, the study found. One reason, Delisle said, was that the private loan industry dried up during that period, in large part because of state and federal government crackdowns, and PLUS loans filled the gap.

Increasing Federal Role

Delisle attached several caveats to the report. The data feature only full-time, not part-time, students. And the NPSAS is conducted every four years, which means the most recent numbers are somewhat dated. The study also had to use data from the Delta Cost Project to calculate what colleges report as education costs, which don’t match up exactly with the student-specific data from the federal survey.

The analysis used national averages, which the report noted can obscure important differences in college costs and financing between states and individual colleges.

“It doesn’t speak to the university you know best,” Delisle said..jpg)

The study is a useful assembly of various cross-sectional data, said Daniel Madzelan, assistant vice president for government relations at the American Council of Education. But the fact that low-income students have been mostly insulated from state disinvestment by federal spending increases isn’t that surprising, he said.

“I don’t think there’s much new ground plowed here,” said Madzelan, a former official at the U.S. Department of Education, who added that state budget cuts remain a serious problem. “It’s not that the crisis has passed.”

In addition, Madzelan said stagnant wages among middle-income families may obscure some of the problem.

“For 80 percent of families, they have not seen a real increase in their incomes” over the last decade, he said.

Delisle acknowledged the new study is a somewhat of a counternarrative to widespread concern about state disinvestment. He also said it could add to concerns Republicans in Congress (he previously worked as an aide to a Republican congressman and for the Senate budget committee) have voiced about the “constantly expanding” federal role in higher education.

George Pernsteiner, president of the State Higher Education Executive Officers (SHEEO), called the new study an important contribution to the discussion about college costs, price and who pays.

“It is hard at the nationwide level to draw sweeping conclusions,” he said via email, “but it is important to note that federal policy and programs have helped maintain affordability for community college students and for many of the students at four-year public institutions.”

Pernsteiner also said it was interesting that the report identified an increase in the percentage of costs now paid by loans versus out-of-pocket spending, and that reductions in state and local subsidies affected students differently across income groups, although state and local government subsidies are not allocated intentionally to do so.

“The reason for the difference is probably due to the type of institutions lower-income students are most likely to attend,” he said.