You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

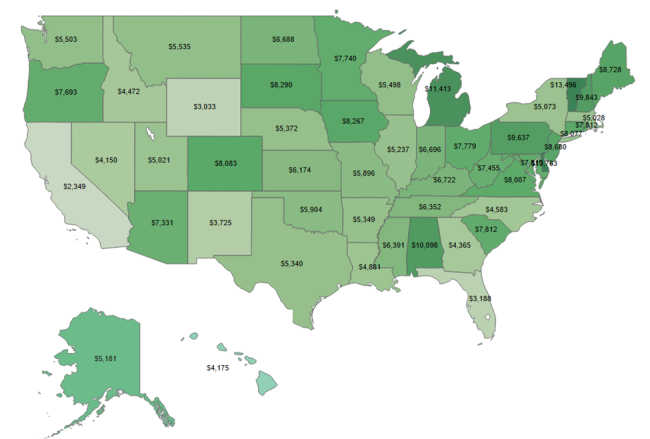

Net tuition revenue per student

SHEEO

When states cut higher education budgets, students make up the difference.

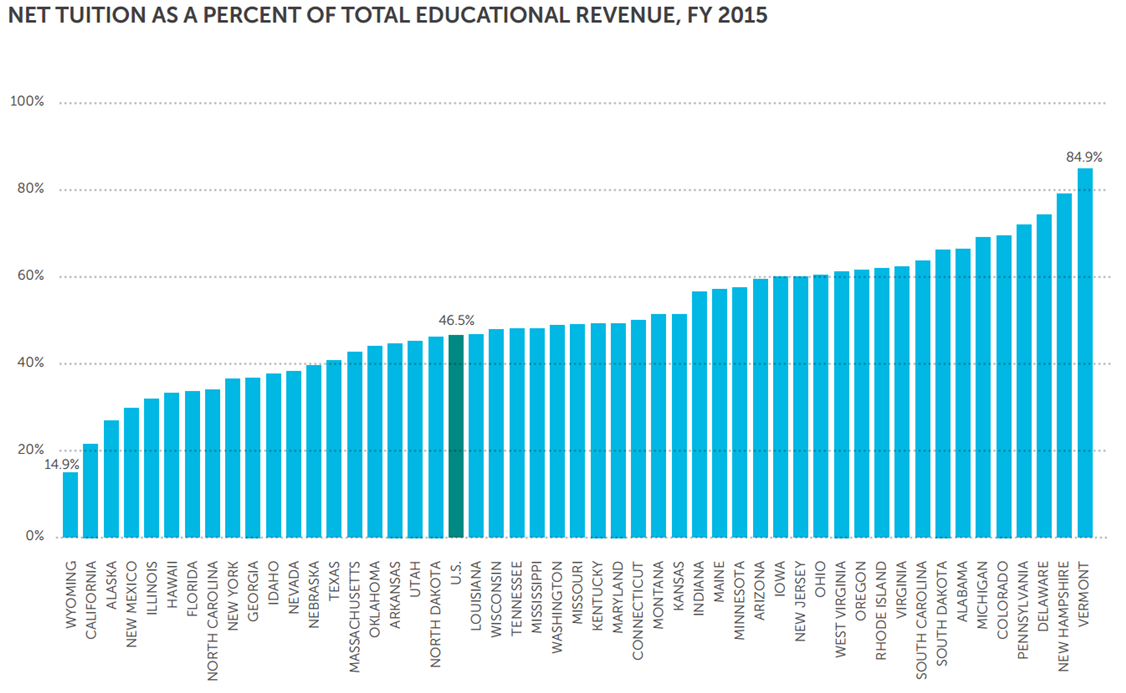

Back in 1990, tuition made up 25 percent of public colleges’ revenue. During the recession, state funding fell and tuition rose -- and by 2013 the proportion of tuition as a contributor to revenue had nearly doubled, to 47.8 percent.

But now, for the second year in a row, the amount of the cost students pay is going down, according to the annual State Higher Education Finance report, released today.

In fiscal year 2015, tuition made up 46.5 percent of revenue, the study found. And while that number isn’t anywhere near pre-recession levels, it means that public higher education is slowly starting to recover.

But the recovery is spread unevenly, in time and in location. In Wyoming, only 14.9 percent of revenue comes from tuition. In Vermont, that number is 84.9 percent. And across the country, there are still 15 states above 60 percent.

“Even if the overall numbers look like there's been a recovery, it doesn’t always feel like that,” said George Pernsteiner, president of the State Higher Education Executive Officers association.

At the same time, 40 states increased their higher education budgets in 2015 -- the most that the researchers had seen in recent years. And while some states are still seeing cuts, Pernsteiner said, “Forty states is a lot of states.”

With the increase in state support, the average per-student support went up 5.2 percent, to $6,966. But while that’s an improvement over last year, it’s still well below the 2008 average, at $8,221. Going back even farther, it’s also well below the numbers from the previous recession, in the early 2000s.

“We hit a double whammy from the last two economic downturns,” said Andy Carlson, SHEEO senior policy analyst and one of the study’s authors.

This year’s increase in per-student spending isn’t just a sign that states are reinvesting; it’s also a result of declining enrollment.

On its own, declining enrollment could actually be a sign of economic recovery, the researchers say. During recessions, people who can’t find work often ride out their stark job prospects by returning for more education or training. “As the recession ends,” Pernsteiner said, “they're able to take those skills that they've honed and take them into the workplace.”

It makes sense, but one could also argue that the middle of a recession isn’t the best time to get a degree. In tough times, funding for higher education is often the first thing to go.

“A lot of people have said it’s the balance wheel of state budgets,” Carlson said. “During downturns, it tends to be cut more significantly.”

Now, as a result of the most recent recessions, public colleges are facing a new normal, the researchers write. Higher education is easier to cut than, say, health care, and those expenses will keep states from fully reinvesting in public colleges.

Jane Wellman, a senior adviser with the College Futures Foundation, said that states tend to budget one year at a time. They spend more on public higher education when the economy improves, but they don’t plan for the future.

“It’s like an accordion,” she said. “When the money’s there, you expand it open. When it’s not, you close it up.”

Wellman wants to see more states thinking long term. Instead of pouring more money into public higher education during good years, they should do more to plan for bad ones.

Looking ahead to 2016, estimates from the annual Grapevine report show state support growing by 4.1 percent. But, as Carlson said, “there are some unique challenges in specific states in 2016.” Illinois and Pennsylvania spent months in budget stalemates, and other states are likely to face new cuts in 2017.

Some states, Pernsteiner said, will continue cutting education budgets significantly -- and over time, those states will face the long-term effects that deep cuts can have on their ability to educate their people.