You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Inside SNHU's Millyard building, where the university's online operations are managed.

Southern New Hampshire University

MANCHESTER, N.H. -- Back when Southern New Hampshire University was still a small regional institution with a modest online presence, Paul LeBlanc, the university’s president, called a meeting with his online team.

The group watched as LeBlanc opened the University of Phoenix’s website, filled in a request-for-information form and placed his cellphone on the table. A few moments later, the phone rang. It was a Phoenix representative calling, ready to help the president enroll in an online degree program.

LeBlanc wanted to show his team what they were up against. He understood that “speed-to-lead” times would become paramount in online admissions. Calling potential students 10, 15 or 30 minutes after they submit an inquiry wasn't good enough.

“We're not where we need to be,” he said.

That was over a decade ago. SNHU representatives now aim to call prospective students so fast that they don’t have time to click away from the university website. The university typically returns 98 percent of new lead calls in under three minutes.

Speed and efficiency have helped SNHU to grow its online enrollment from 3,000 students in 2003 to around 132,000 students today.

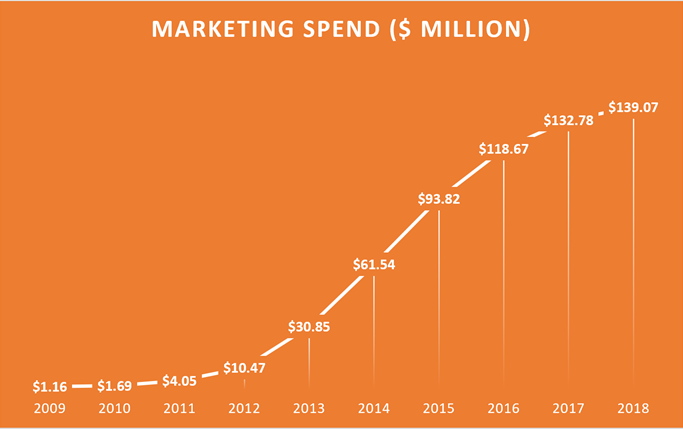

But there is another magic ingredient that has propelled SNHU -- hundreds of millions of dollars spent on advertising and student recruitment.

As competition for students increases, SNHU faces two options to continue growing: spend even more or innovate.

With a marketing spend of more than $139 million last year, LeBlanc is attempting the latter.

An Ambitious Growth Strategy

During his 16-year presidency, LeBlanc has transformed SNHU from a sleepy regional college to a slick online behemoth.

He is candid about the fact that for-profit institutions such as Phoenix helped pave the way.

“We learned a lot from the early days of Phoenix -- how to be more student-centric, how to be more customer service-oriented, how to improve our processes and use data better,” he says. “All things that higher ed, not surprisingly, [was] never good at.”

At its height in 2010, the University of Phoenix enrolled more than 470,000 students. Inside Higher Ed reported that Phoenix’s enrollment likely dipped below 100,000 last year.

When it started out, Phoenix did good work, says LeBlanc. Things started to shift when the university’s parent company, Apollo Education Group, became publicly traded in 1994. “Suddenly there was all of this pressure to satisfy shareholders’ expectations around growth. If you have to make your numbers and they aren’t looking good, you might start to do things that aren’t great in order to make that number.”

Phoenix continued to grow for many years after Apollo went public, as did many other large for-profit institutions. But the sector's sometimes aggressive recruiting tactics and relatively high student debt levels attracted the attention of policy makers, who began tightening regulations.

While political scrutiny of for-profits, particularly their student recruiting and business practices, has contributed to a long slide in Phoenix’s student numbers, online enrollment at the nonprofit, private SNHU continues to soar.

With more than 130,000 students, SNHU is one of the three biggest universities in the U.S., alongside Arizona State University and Western Governors University.

SNHU has no shareholders to satisfy, and the university's trustees aren't pressuring the president to grow enrollment. He is nonetheless pursuing aggressive expansion, with a goal of enrolling 300,000 students by 2023.

LeBlanc says this target isn’t firm. “We put a number out there because when you do strategic planning, you want to give some sense of scale.”

The desire to grow quickly is driven by the institution’s mission of providing affordable and accessible higher education to everyone. “When somebody asks, ‘How big can you get?’ or ‘How big do you want to get?’ I say, I want to be as large as possible to help as many people as possible without any slippage in the things we value most.”

If student satisfaction or graduation rates went down, LeBlanc says he would have no problem tapping the brakes. “I know with certainty that the board would support that, too.”

An Expanding Workforce

An Expanding Workforce

To keep pace with its growing enrollment, SNHU has to constantly hire new staff members. The university is close to becoming one of the 20 biggest employers in the state of New Hampshire and is planning to open a new operations center in Tucson, Ariz., with 350 employees who will support students living on the West Coast.

Here in Manchester, just a few miles south of SNHU’s traditional 350-acre campus, the university’s impact on the city is clear. SNHU-branded buses shuttle employees and students between campus and university buildings downtown. The SNHU Arena, previously the Verizon Wireless Arena, hosts university commencements and sporting events. In the former industrial heart of the city, an area known as the Millyard, SNHU has built a parking lot with 1,700 spaces to accommodate its expanding workforce.

A vast former textile mill nearby serves as the nerve center of SNHU's online operations. Inside, hundreds of inquiry-response representatives, admissions counselors, financial aid counselors and academic advisers work to enroll new students and keep existing students on track. Though these employees don headsets, the “mill” doesn’t feel much like a corporate call center. There is a hum of activity rather than a roar. Desks are liberally decorated with photos and twinkle lights. Staff, many young locals, talk animatedly with students and colleagues.

Working alongside the student support staff are IT employees and a large marketing team consisting of social media managers, digital marketing specialists, data analysts and creative staff. The teams are deliberately located close together so that they can collaborate, says Alana Burns, chief marketing officer at SNHU.

Burns doesn’t think about marketing as one moment in time, but a continuum. Every aspect of the student experience matters.

There is a principle in marketing known as the four moments of truth -- four points in time when users form an impression of a brand, product or service. Before someone decides to attend SNHU, they have to decide they want to attend college. This is the zero moment of truth. The first moment of truth occurs when someone sees an SNHU ad on TV or clicks a link online and decides whether or not to enroll. The second moment of truth is their experience at the university. The third and ultimate moment of truth is whether they recommend SNHU to friends and family.

“You have to get marketing right all the way across,” says Burns.

Recommendations are a powerful tool, and they don’t happen if students have a bad experience. This year, 20 percent of new students heard about SNHU through word of mouth. Burns wants that number to keep growing.

“The most important investment that SNHU makes is in the student experience, in the advising, the academic design, the streamlining of the admissions process,” says Burns. “We don’t have Division I athletics, or a 200-year history or a huge endowment. But we do have a huge alumni base, and if they didn’t talk positively about their experience, it wouldn’t matter how much money we spent -- we wouldn’t keep growing.”

Building a National Brand

SNHU didn’t become a national institution overnight. It wasn’t until around 2011 that the university made a concerted effort to raise its profile across the U.S.

Online enrollment stood at around 12,000 students in 2011, an increase of around 9,000 students since LeBlanc joined in 2003. Over time, the university added new programs and refreshed old ones. But online students were still concentrated in New England. To keep growing, SNHU would need to cast a wider net.

Although online education allows students to be located anywhere, many people choose to study at institutions close to where they live. A recent survey by Learning House found that two-thirds of online students pick colleges with locations within 50 miles of their home. Students like to attend institutions with connections to their community and local employers -- somewhere they feel they know.

To attract students from outside New England, SNHU had to find a way for people thousands of miles away to connect with the institution. Cable TV ads played a pivotal role in raising the profile of the institution. Early ads emphasized that SNHU offered a “traditional” education that could be completed alongside a full-time job. The ads also stressed that SNHU is nonprofit.

“Earn a degree you can be proud of, at a price you can afford,” says one ad from 2011.

There is some internal debate about whether ads need to stress that SNHU is nonprofit. Audience testing suggests students don’t care much about the tax status of an institution, but the message is important to the people who work at SNHU, Burns says. TV ads help to attract not only students, but also new talent.

Students who overcome adversity to achieve their educational goals have become a prominent theme in SNHU’s marketing campaigns. “We want you to see yourself in our ads,” says Burns.

One of the university’s most successful TV ads showed footage of a real commencement ceremony where LeBlanc asked students to stand up if they are the first in their family to attend college, if they are mothers, veterans or active-duty military service members. A huge portion of the audience stands. The ad has aired nationally more than 54,000 times, according to media measurement company iSpot.

Another memorable ad shows an SNHU-branded bus touring the country and delivering diplomas to students who couldn’t attend graduation in person.

The bus has become a popular motif in SNHU ads, and a fixture at university events. University officials say enthusiasm for this symbol is palpable. “I think if people could hug and kiss that bus, they would,” says Phaedra Schmidt, associate vice president of marketing and creative strategy at SNHU.

The SNHU marketing team dipped its toes into the world of TV advertising with care -- performing small tests and evaluating the results. Before targeting cable networks, they picked a handful of cities and showed ads for 10 weeks on regional TV stations. “We wanted to see if people would come take a look at us, and the answer was an immediate yes,” says LeBlanc.

SNHU soon shifted to cable TV channels such as MTV. “It was an efficient way to get our name in front of everybody,” he says. “National media buys became our cornerstone.”

Television advertising is expensive and only works if it’s sustained. “If you do one burst of advertising and say, ‘How did we do?’ it’s not going to look very good, and it’s going to feel very expensive. If you keep showing ads month after month, year after year, you start to build brand traction. That’s when that person in California says, ‘Oh yeah, I’ve heard of that place,’” LeBlanc says.

There wasn’t a specific point at which SNHU shifted from a regional to a national university, says LeBlanc. “When we saw enrollment climb at the furthest reaches of the market, when we started to move from hundreds to thousands of students in places like Texas, Florida and California, that’s when we realized we didn’t have primary and secondary markets anymore.”

A Changing Media Strategy

Over time SNHU’s brand has evolved significantly. “Eight or nine years ago, we would introduce new programs and there were no students yet. We didn’t have those student stories,” says Schmidt.

In the past SNHU would use actors and stock photography to represent its students, but that didn’t feel authentic, says Schmidt. Now the university has an abundance of real stories to choose from. One of Schmidt’s favorites is Amy Craton, a 94-year-old woman in Hawaii who completed her degree after 54 years, with a 4.0 GPA.

“We rely a lot on brand ambassadors and like to share stories that are simple and human and inclusive. What you see is so real. We want you to have that emotional connection with our students and feel proud of them,” says Schmidt.

While SNHU continues to produce more TV ads than many (if not all) other universities, the marketing team knows viewing habits among young adults are changing fast.

“We’re thinking more and more about YouTube,” says Schmidt. “In a six-second ad, you only have time to send one message. Figuring out how to do that is a lot of fun for us.”

Work on ad campaigns begins months before they are ever seen by the public, says Schmidt. “We might develop 30 ideas and only one will go to market. We’re still learning what the most impactful and relevant messages are all the time.”

In a push for greater efficiency, Burns moved all media buying in-house in July. The university previously used an agency to plan and purchase ad placements on different mediums and measure their efficacy. “It gives us more control, and we get to see everything so that we can make more informed decisions,” she says. Video production is one of the few areas the university still outsources. “It’s just not something that we need every day.”

In terms of spending, digital marketing has overtaken traditional marketing. The “supermajority” of the digital marketing budget is spent boosting SNHU’s visibility on search engines, says John Lucey, the university’s vice president of digital performance marketing and marketing technology. The rest of the budget is dedicated to social media advertising -- something the university didn’t do five years ago. Most of these online ads are text based and don't involve video.

SNHU’s social media marketing is focused on Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn, with Twitter, Snapchat and Pinterest playing a less prominent role. “We’re everywhere that students are,” Lucey says.

Everything the marketing team does, whether in digital or traditional mediums, is informed by data. Many staff come from an e-commerce background, says Lori Szydlik, vice president of web for the university.

“We have to make a convincing case for more investment, and that means lots of testing to get the data that proves what you’re doing works,” she says.

“Right now there’s a hyperadoption of new technology, a landscape of new digital experiences,” says Szydlik. “We’re not just competing with other universities, but competing with what [students are] expecting from a web experience.”

In the past year and a half, SNHU has made considerable upgrades to its website. “Users expect an app-like experience when they visit your webpage,” says Szydlik, “and that means everything has to be superfast. Page load time is really important.”

The SNHU website has historically taken between 4.5 and 3.7 seconds to load. Now it’s sub-three seconds. Everything the online team does is mobile first, says Szydlik. And each layout, font and color is carefully optimized with A/B testing.

A 2020 website refresh won’t present radical changes. “It’s more future-proofing,” says Szydlik. But bigger changes are on the horizon. “One of the most difficult things we’re working on is how to personalize the web experience, but not in a creepy way.”

With technology changing fast, and nationwide 5G on the way, the team is constantly trying to stay ahead of the curve. “It’s exciting work, but you have to have a good ability to adapt to change. You have to get used to not being the expert,” she says.

For many years, for-profit colleges spent more on marketing than nonprofits, but two years ago, that changed.

“Twenty sixteen was the first time in history that private nonprofit expenditures exceeded those of for-profits,” says Bob Brock, president of the Educational Marketing Group, a brand agency that works with colleges and tracks industry spending.

According to EMG and Kantar Media data, the for-profits spent $607.7 million on marketing in 2016, while private nonprofits spent $611 million. The scales tipped because for-profits lost market share, says Brock. And fewer of them existed after waves of closures. Meanwhile, nonprofits have experienced huge growth online in an increasingly competitive arena.

Between 2014 and 2016, Brock estimates that for-profits lost around 25 percent of their online students. Over the same time period, online education at public, nonprofit institutions grew by roughly 15 percent. Growth at private nonprofits was around 35 percent, largely driven by SNHU, WGU and Liberty University, he says.

Phoenix still spends much more than any other institution on marketing, says Brock. But SNHU comes in second. And SNHU is “in a league of its own” when compared with other private nonprofits, he says.

In the fiscal year ending June 2018, SNHU reported a total revenue of $807 million with a net surplus of $133 million after expenses. The same year, SNHU spent $139 million on advertising and promotion, according to its latest federal tax form. The document lists advertising payments of almost $47 million to Google and just over $85 million to Mediassociates Inc., a media buying and planning agency.

A SNHU representative said that the university’s marketing budget, which she reported as $133 million in fiscal year 2017, includes market research, website operations, communication with current students, social media, student experience, signage on campus, employee communications and video and creative teams.

It’s not easy to track exactly how much institutions spend on marketing, says Brock. Different institutions include different things in their marketing budgets, making it difficult to pin down precisely what is spent where. Comparing marketing budgets across different institutions is also difficult for that reason, but he estimates that the average private nonprofit spends under 5 percent of its annual revenue on marketing. SNHU is spending over 17 percent.

Brock says SNHU’s approach to marketing is highly effective. “They are likely seeing a very good return on investment,” he says. “They produce A-plus-quality materials, which is important, because audiences today are sophisticated consumers. We’ve all seen millions of ads and can judge really quickly if someone put in the effort or tried to do something cheap.”

Stephanie Hall, a fellow at the Century Foundation, would like to see more questions asked about what an appropriate level of spending is for higher education marketing.

In a report the foundation published earlier this year, Hall examined how much institutions spend on student instruction, with disappointing results for the universities with the largest online enrollments. “Why is instructional spending low at online colleges?” asked Hall in her report. “The most charitable explanation, which is likely at least partly true, is that while online education has the potential to create efficiencies in instruction, it also requires more spending on information systems and other forms of student support.” A less charitable explanation is that “low-spending, high-tuition online education is a cash cow” with large chunks of tuition subsidizing intensive marketing, generating high levels of profit for investors or funding other university projects, wrote Hall.

If an institution spends more on marketing than instruction, this should raise a red flag, Hall says. But she acknowledges that tracking institutional spending on marketing and instruction can be challenging as institutions include different things in these budgets. SNHU, for example, includes student support services in its marketing budget. Stricter reporting requirements would help increase transparency, she says.

While politicians have for many years attempted to curb what for-profit institutions may spend on marketing, nonprofits historically have escaped the same scrutiny. This may be changing.

At a meeting of the Education Writers Association in 2019, Diane Auer Jones, U.S. deputy under secretary of education, described aggressive marketing techniques as “the biggest consumer protection issue” in higher ed.

Two bills introduced in the U.S. Congress last year aimed to limit how much federal funding institutions may spend on marketing. This year the PROTECT Students Act, included a provision that would prevent any federal student aid from being spent on recruiting or marketing activities.

LeBlanc believes this legislation, if passed, would impact smaller colleges more than large ones like SNHU that have diverse revenue streams. He recognizes, however, that marketing is an area that could become an increasing focus of policy makers.

For the past three years, SNHU has kept its marketing budget flat to curb its student acquisition cost, a ratio which the institution calculates by dividing its total marketing budget by the number of students enrolled.

Student acquisition cost is an important metric for online programs. Many institutions have seen this figure increase sharply as marketing costs have gone up and competition for students has intensified. “When we get that number to go down, as it is for us right now, that feels really good,” says LeBlanc.

The acquisition cost per enrolled student at SNHU was $1,134 in 2018, down from $1,240 the previous year, the university reported.

It isn’t clear how long SNHU will be able to do this and keep growing. “We’re going to hold the line for as long as we can and see how it plays out,” says LeBlanc.

Word-of-mouth recommendations, increased use of social media and workforce partnerships are helping SNHU grow without increasing traditional marketing costs. SNHU’s partnership with Walmart through Guild Education, for example, is expected to enroll hundreds of new students in its first semester. “We have over 100 of these types of partnerships, and we continue to see the number of students enrolled with us grow,” he says.

Word-of-mouth recommendations, increased use of social media and workforce partnerships are helping SNHU grow without increasing traditional marketing costs. SNHU’s partnership with Walmart through Guild Education, for example, is expected to enroll hundreds of new students in its first semester. “We have over 100 of these types of partnerships, and we continue to see the number of students enrolled with us grow,” he says.

Critics of big marketing budgets don't see the big picture, says LeBlanc.

“I think marketing is seen in higher ed as this crass thing, and the more you spend on it, the poorer quality you must be. That feels like such a failure to recognize the reality of how we compete and how we get in front of people,” says LeBlanc. “If you want to build a national footprint and serve as many people as possible, tell me how else to get our name in front of everyone?”

Marketing is aligned with SNHU’s mission, LeBlanc says, because it helps the university reach large numbers of potential students.

“None of us became educators to spend time thinking about marketing. It doesn’t feel commensurate to what we do,” he says. “But when we connect with a student that might not have found their way to us otherwise, who may have struggled and failed elsewhere, that feels like a good investment.”

Dwarfing Competition

It’s difficult to get a sense of how many institutions are losing students to SNHU. But Abu Noaman, CEO of Elliance, a digital marketing agency, says many small nonprofit colleges are struggling to grow their enrollment.

“That’s the No. 1 challenge that everyone has,” he says. “They know they should be growing at a certain pace, but they’re seeing competitors grow at a much faster rate.”

Many colleges underestimate how much they should spend on marketing, says Noaman. “You can’t spend less than 5 percent of your revenue on marketing and expect to compete with the nonprofit giants -- they’re eating these smaller colleges for breakfast, lunch and dinner.”

He says colleges also tend to spend their marketing dollars in the wrong places. SNHU may have boosted its brand with television ads, but TV spots are expensive, take a long time to see returns and don’t reach young audiences.

Instead, digital marketing is where most institutions should be focused, he says. Every institution is different, but most would benefit from increased search engine visibility. “Most people never go beyond the first page of Google search results,” he says. “You want to be near the top.”

Colleges with limited budgets have some options to compete. For example, Noaman says they could easily revamp “anemic-looking” academic program pages to paint a fuller picture of what studying to earn that degree at that college really looks like. They could also start telling compelling student stories through social media.

“Young people are smart,” he says. “They don’t really want to be spammed or marketed to. They want you to win their hearts and minds.”

Many colleges approach marketing with an institutional mind-set, and that’s a mistake, says Noaman.

“Colleges often think they are the hero of the journey, when really they are just enablers. It’s the students, alumni and faculty who are the heroes,” he says. For many institutions, changing that mind-set requires a big cultural shift.

“It’s easy to burn through a lot of money very quickly if you don’t know what you’re doing,” says Kenneth Hartman, interim vice president of Rowan Global Learning and Partnerships, the online arm of Rowan University -- a public university located in New Jersey.

Hartman was previously president of Drexel University Online. His goal for Rowan is to grow online enrollment. But Hartman recognizes he can’t take the same approach that SNHU did -- the space is much too crowded now. “I can’t just throw a big net out and catch lots of fish. There has to be a lot of science, a lot of strategy,” he says.

Rather than developing new online degrees, Hartman’s focus will be on developing online certificates and short courses that focus on career advancement. “People want to take smaller bites out of the apple,” he says. “They might not know if they’re ready for an M.B.A., or they might already be saddled with debt.”

Too many colleges have developed offerings that are not distinctive, says Hartman. “The reality now is that online courses, particularly in general education, have become a commodity. Why would you spend thousands of dollars developing an online course in psychology when a student can go to StraighterLine and take it for $99 a month?”

Joshua Pierce is CEO and co-founder of the College Consortium, a tech company that offers institutions an online course-sharing platform and services such as academic credit transfer.

Like Hartman, Pierce thinks the online education space is crowded with similar offerings. If more colleges pooled their general education resources online, they could free up resources to develop more distinctive offerings. “You don’t have to do online the way everyone has done online,” he says.

SNHU, ASU and others have been so successful online because they had leadership that took a “very long view,” says Pierce. They built a lot of capacity in-house over many years, and now have lots of capital to play with. It would be difficult for any small college to catch up.

But Pierce says smaller colleges can be successful online. “They just have to work with what they’ve got.”

| Year | Marketing Spend | Revenue | Marketing Spend as % of Revenue | Total Enrollment (Degree and Non-Degree) | Student Acquisition Cost (Marketing/Enrollment) |

| 2009 | $1,160,906 | $115,508,668 | 1 | 11924 | $97.36 |

| 2010 | $1,685,584 | $115,692,505 | 1 | 12648 | $133.27 |

| 2011 | $4,049,552 | $142,728,916 | 3 | 15333 | $264.11 |

| 2012 | $10,470,622 | $166,278,203 | 6 | 21535 | $486.21 |

| 2013 | $30,852,125 | $235,127,834 | 13 | 33899 | $910.12 |

| 2014 | $61,536,138 | $352,544,582 | 17 | 55683 | $1,105.12 |

| 2015 | $93,815,069 | $507,626,312 | 18 | 84881 | $1,105.25 |

| 2016 | $118,667,734 | $581,366,224 | 20 | 100353 | $1,182.50 |

| 2017 | $132,777,855 | $690,158,280 | 19 | 121582 | $1,092.08 |

| 2018 | $139,067,676 | $806,676,841 | 17 | 140441 | $990.22 |

Limited Room at the Top

Several institutions have tried and failed to go national with online programs, says LeBlanc. The University of Illinois Online, Colorado State University Online, the University of Florida Online and others have struggled to realize their goals, despite having strong, nationally known brands.

More players with a national footprint are likely to emerge. The University of Massachusetts, for example, is planning to launch a national online college to compete with SNHU and others.

But LeBlanc thinks new competitors will struggle to reach his institution's scale. Overall enrollment for adults in higher education isn't growing very much.

Colleges that can go national quickly are the ones that already have a national brand, says LeBlanc. The reason that some don’t succeed has to do with governance, politics, status, what they charge and many other reasons, he says.

“If you’re a school looking at us today and saying, ‘We’re certainly as good as, maybe a little bit better known than SNHU was 10 years ago -- we should do what they did,’ I’m not sure that’s the right playbook.”

If he were to start over in today’s environment, LeBlanc says he would again try to keep costs down as much as possible.

“We haven’t had a tuition increase online in years,” he says. “If you are going into this space thinking that you’ll be able to charge as much or more online than on-ground, you’re probably misguided. You have to start thinking aggressively about supply and demand and the continued downward pricing pressure on programs.”

One big thing he would do differently would be to build a more robust catalog of microcredentials and nondegree offerings tied to high-demand jobs.

Rather than asking how to take what SNHU does on-campus online, LeBlanc says he would ask, “What’s the highest-demand area that local regional employers have and how can I solve their problems as quickly as possible?”

Helping employers is a win for learners, as they want to secure new jobs quickly. “One of the things that is daunting for any online learner pursuing a degree is that there’s quite a deferred payoff.”

SNHU’s campus has transformed during LeBlanc’s presidency. He inherited a “pretty tired” infrastructure, but now the campus is filled with striking modern buildings.

People often assume the campus improvements took place only after SNHU hit it big online. But that isn’t the case. SNHU commissioned a campus revitalization plan in 2004 and began construction using bond dollars. “That plan and those investments began well before online took off,” he says. “Online just added rocket fuel to the process.”

Unlike WGU and several for-profits before it, SNHU so far has avoided opening satellite campuses close to where its students live.

But the university’s acquisition last year of nonprofit LRNG may change that. The Chicago-based organization has been helping young people find job opportunities by encouraging them to acquire digital badges. A test site in Birmingham, Ala., has been particularly successful and could become SNHU’s first “mini-site,” says LeBlanc.

“Cost is still keeping a lot of people out of higher education,” he says. “There’s not only poverty of finance, but poverty of aspiration -- we’ve got to help people see themselves in higher ed, and maybe it has to look different to work for them. We’ve been learning a lot from LRNG in that respect.”

While SNHU’s campus is a major draw to prospective students who want to feel they are studying somewhere “real” even when pursuing an online degree, few students mix studying online with studying on campus.

“We’re just not built for that,” LeBlanc says.

In the future, LeBlanc would like to see the two modalities become more fluid.

“Students could choose to live on campus but take all their courses online. Someone could be taking courses online but do a residency on campus,” he says. “We don’t make that easy now. We’re still in a campus-versus-online binary, and maybe it’s the wrong binary.”

SNHU is preparing to change, but in at least one respect, the university is already exactly where it needs to be: speed-to-lead times. It took one minute and 37 seconds for a University of Phoenix admissions representative to call us. SNHU took 35 seconds.