You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

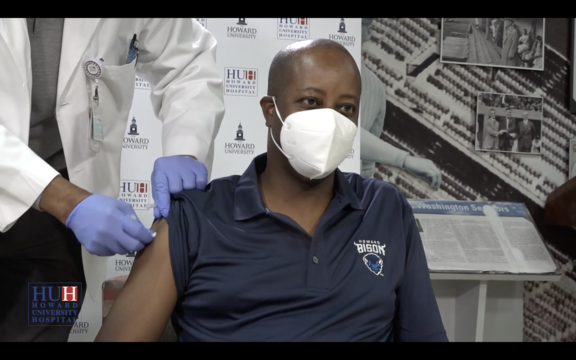

Howard University president Wayne A. I. Frederick receives a COVID vaccine.

Courtesy of Howard University

Donald Alcendor, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at Meharry Medical College, a historically Black medical school in Nashville, Tenn., is studying an antiviral treatment for COVID-19 in his lab. But his work isn’t confined to the lab: he’s also community liaison for Meharry’s Novavax vaccine trial. In that role he goes out to businesses, barbershops and beauty salons frequented by African Americans and Latinos to talk to community members about the COVID-19 vaccines and answer their questions in what he describes as a “transparent and culturally competent way.”

“There’s a fair amount of vaccine hesitancy out there, particularly among brown and Black communities,” said Alcendor, who is Black. “They want their questions answered, and they want their questions answered by someone who looks like them, if you know what I mean. The idea is Meharry Medical College is an important place to do just that -- to answer their questions and to provide them with a vaccine or be part of a vaccine trial.”

Academic medical institutions and public health schools, including minority-serving institutions like Meharry, are taking leading roles in confronting vaccine hesitancy in minority communities. African Americans, Latinos and Native Americans are far more likely to contract COVID-19 and to die if they do compared to their white counterparts. Black Americans are 1.4 times more likely than white Americans to contract COVID, 3.7 times more likely to be hospitalized and 2.8 times more likely to die from it. Latinos are 1.7 times more likely to contract COVID, 4.1 times more likely to be hospitalized and 2.8 times more likely to die.

But as the first two COVID vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna have become available, members of underrepresented minority communities report higher rates of vaccine hesitancy. New data released last week by the Kaiser Family Foundation’s COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor project show that while the share of people who want to get vaccinated “as soon as possible” has increased across different racial and ethnic groups since December, it is still substantially higher for white adults (53 percent) compared to Black (35 percent) and Hispanic adults (42 percent).

Other data from a multi-university research group finds that Black and Hispanic survey respondents are more likely to believe misinformation about the vaccine, and are more likely than Asian Americans and whites to believe that certain false statements about the vaccine -- for example, that it contains microchips that can track people -- were accurate.

Experts point to a wide range of reasons for higher rates of vaccine hesitancy among Blacks and Hispanics, including the medical profession’s sorry legacy of mistreatment of Black people, the fear vaccination could be used for immigration enforcement purposes and the inequities minority communities continue to face in terms of access to health care.

David M. Carlisle, the president of the Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, a historically Black graduate institution in Los Angeles, said he was struck by how often laypeople cite the unethical Tuskegee syphilis experiments performed on Black men between 1932 and 1972 as cause for concern.

“It’s only natural that communities of color that have been underserved by the health-care system would be suspicious about something new,” Carlisle said. In December, Carlisle joined with the presidents of the nation's other three historically Black medical schools, along with the presidents of the National Black Nurses Association and the National Medical Association and others, in signing “A Love Letter to Black America,” affirming respect for Black lives and urging Black Americans “to join us in participating in clinical trials and taking a vaccine once it’s proven safe and effective.”

“Our community is being ravaged disproportionately by COVID-19,” said Carlisle. “This is a situation that’s very personal, and that’s why we want to assure people that the way we can beat back COVID-19 is by optimizing participation in vaccination programs to the fullest extent possible.”

"This is really about saving our lives," said Anita Jenkins, CEO of Howard University Hospital, in Washington, D.C. "Too many of us have died."

Howard created a public service announcement about the vaccines aimed at Black Americans. Across the country, academic medical professors and leaders and public health scholars are engaged in advocacy, outreach and research on the issue of vaccine hesitancy.

A research initiative at the City University of New York Graduate School of Public Health & Health Policy, CONVINCE USA, is seeking to better understand and address public concerns about COVID-19 in order to better inform the development of communication and outreach strategies.

"Clarity and transparency and consistency in the message is very important," said Ayman El-Mohandes, the dean CUNY's public health graduate school. "We have found that in many instances people are less certain of accepting a message if there are conflicting messages and if they feel like decisions are being made without full transparency and without the community understanding the science base or the evidence base."

Health professionals routinely emphasize the importance of working with community groups and religious and political leaders to get the message out. The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston held an event last weekend at one of its clinics in a largely minority community, livestreamed on Facebook, where a number of elected officials received vaccines.

“We have to build on the relationships we have with many respected leaders in the community and use them as partners to help educate the community,” said LaTanya Love, interim dean of education of McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and executive vice president of diversity for UTHealth. “We did an event with former heavyweight boxer champion George Foreman; he received his vaccine at one of our clinics. It was a way to use a well-respected celebrity figure in the community to reassure people who are hesitant.”

Shiva Bidar-Sielaff, vice president and chief diversity officer for UW Health, the academic medical institution for the University of Wisconsin, said the health-care center has partnered with community groups to organize conversations about the vaccines with doctors who are trusted in the Black and Latino communities.

"Making sure this information is given by trusted sources within the community itself is really critical," Bidar-Sielaff said. She added that the health-care system is in the process of hiring COVID vaccine patient educators to reach out directly to primary care patients, including two each who will focus on Black and Latinx patients and one who will target to Hmong patients.

"It boils down to what we call right message, right messenger work," said Virginia Davis Floyd, an associate professor of clinical community health and preventive medicine at the school of medicine at Morehouse School of Medicine, a historically Black institution in Atlanta. The medical school received a $40 million federal grant to coordinate a network of national, state, territorial, tribal and local organizations to deliver COVID-19-related information to racial and ethnic minority communities who are being hardest hit by the pandemic.

"We have to be consistent with our messaging, and we have to be out there for the long term," said Amelie G. Ramirez, professor and chair of the Department of Population Health Sciences at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, a Hispanic-serving institution, and director of the Institute for Health Promotion Research there.

"For the long term, this is an issue we can’t ignore," Ramirez said. "COVID has just put a spotlight on health disparities. We need to look to the future and look at what does systemic racism look like in our health-care system and what can we do to improve that so we can provide more equitable health care to our entire population?"