You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

“It’s a really interesting-sounding technical problem to figure out how you would create a lab in a virtual space,” said Nicholas Evans, chair and associate professor of philosophy at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell. “But it sounds more like a science experiment in its own right than a settled piece of pedagogy.”

Dreamscape Learn/ASU

Arizona State University had a problem. Many students arrived on campus eager to study science, technology, engineering and mathematics subjects. But by the end of their first year at the university, nearly half switched to non-STEM majors or left the university altogether, according to Annie Hale, executive director of the Action Lab at Arizona State. Though that statistic tracked with the national trend, campus leaders were concerned that these students were no longer on track for high-paying STEM jobs.

“We measure ourselves by our charter of who we include and not who we exclude,” Hale said—the institution has been designated a Hispanic-serving institution by the U.S. Education Department.

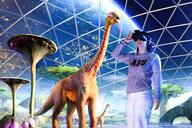

To address the problem, Arizona State turned to an unlikely source: Hollywood. Dreamscape Immersive, a virtual reality company co-founded by an individual responsible for blockbuster movies such as WarGames and Men in Black, partnered with the university to create Dreamscape Learn. The new educational company revamped Biology 181—the university’s introductory course. In the new version, which was offered first in the spring of 2022 alongside the original version, immersive VR experiences replaced traditional labs.

When researchers at the university later compared outcomes from the two courses, they found that students, including those who have been historically underrepresented in higher education, performed significantly better in the VR version of the course. Those in the VR labs enjoyed getting to “know” named cartoonlike animals through immersive, cinematic stories. Many even found themselves crying when—spoiler alert—the matriarch of a dinosaur herd dies.

Arizona State deemed the experiment a success. As a result, beginning last fall, the university replaced all of Bio 181’s traditional labs with the virtual reality version.

But some academics caution against the wholesale replacement of traditional labs with VR labs for training emerging scientists. Though students are often enthusiastic about immersive VR experiences, the technology has shortcomings in replicating the quality and fidelity of scientific pursuits. Arizona State’s experiment offers promising results, including in boosting success among underrepresented students. But the experiment is in an early stage, and the long-term outcome is yet to be determined.

“It’s a really interesting-sounding technical problem to figure out how you would create a lab in a virtual space,” said Nicholas Evans, chair and associate professor of philosophy at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell. “But it sounds more like a science experiment in its own right than a settled piece of pedagogy.”

For VR in Science, Lots of Enthusiasm, Mixed Learning Outcomes

Virtual reality technology can help students visualize abstract concepts, simulate first-person encounters, practice skills and take virtual field trips. Such sensory, narrative experiences can improve student enthusiasm for course content, which in turn may positively impact motivation and engagement. Further, in biology, VR can boost students’ empathy for nature and offer insight that is inaccessible by other means.

In science classrooms, students are generally enthusiastic about immersive virtual reality experiences, but the learning outcomes are “mixed,” according to a 2022 review of 64 studies considering how science educators design, implement and evaluate VR-based learning. (Most of the studies in the review focused on biology classrooms, though the Arizona State study was not part of the review.)

Educators often do not align their rationales for adopting VR with course learning outcomes, according to the review. For example, some instructors used three-dimensional visualization to help students “see” abstract science concepts, which consistently amazed students. But the students were often passive recipients of the information, with limited opportunities to interrogate ideas, construct knowledge or build scientific understanding from the experience.

Some, including those who see opportunities for VR-enhanced biological learning, caution against the wholesale replacement of traditional labs with VR labs for instruction. That’s because VR designers can only add scientific content that they already know. As a result, students pursuing science in VR may be conditioned to think that unexpected results are wrong results.

“In biology, unexpected results may not be wrong results,” Evans said. “They may be new discoveries.” When students “react to a system where all of the outcomes are determined, that really stops it from being science.”

Some tasks, such as learning how to set up equipment, may be good candidates for modeling in VR, Evans suggested. But others, such as relying, in part, on intuition to ensure safety or recalling that the growth factor purchased long ago may now be expired, makes life in a real lab quirkier.

“There’s only so much we can model in virtual reality right now,” Evans said. “I would be deeply suspicious about the degree to which the virtual reality labs would mirror the experience of working in a physical laboratory.”

John Vanden Brooks, professor and associate dean of immersive learning at Arizona State, often fields questions from VR skeptics about biology students’ alleged needs to learn to pipette. But he and fellow biologist Mike Angilletta—also a professor and associate dean of learning innovation at Arizona State—have not pipetted in their careers.

“It’s very hard for me to argue that pipetting is a foundational skill of all biologists,” Vanden Brooks said, adding that students can learn pipetting if or when they need that skill. “But what’s foundational for all biologists is building a foundational model that I can make a quantitative prediction about, that I can analyze and go back and apply. Those are the skills that [Arizona State’s VR] lab-based curriculum is teaching” by way of fostering students’ emotional connections through cinematic narratives followed by group work.

The review highlighted that some studies concerning the effectiveness of VR in science classes overrelied on self-reported (i.e., student-reported) measures of learning. Also, many students reported positive learning experiences even when they had difficulty learning with VR. Here, the researchers hypothesized that social desirability bias—a tendency to give a socially desirable answer rather than one that reflects their true feelings—may have played a role.

“There is some promise, and there is some also some peril,” said Douglas McCauley, associate professor of ecology, evolution and marine biology and director of the Benioff Ocean Initiative at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “We need to be eyes wide-open as we consider these tools for [science] teaching.”

ASU’s Promising Results, With Caveats

In a recent VR experience, ASU biology students found themselves in a virtual habitat for astelars—imaginary starfish-like creatures that change colors.

“Every creature is made up. Every organism is made up. Every bacterium is made up. There aren’t any earth-based organisms that exist in the biology curriculum,” Vanden Brooks said. “Students are given novel problems that they care about solving that they cannot google the answer to.” In the VR, students went on a journey to investigate why the astelar population is in decline.

Upon removing their goggles, the students gathered in small groups to consider data and model scenarios related to whether the species might fare better in a physically hot environment or in a predator’s environment. As the group hovered over a spreadsheet flush with data, one student offered a proposed solution.

“Don’t do that!” another student responded as Hale and her team looked on. “You’re going to fucking kill the astelars!” That was the moment that Hale understood that VR fostered the students’ empathy for the (imaginary) creatures.

“I’ve been blown away by students’ reactions,” Hale said. “The VR is the glue that’s really engaging the students and inviting them to participate in the curriculum, willingly excited to look at Excel spreadsheets.”

In Arizona State’s spring 2022 experiment, nearly 500 of the 660 enrolled students consented to participate in the study exploring the differences between the VR and non-VR versions of the lab. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the groups, and the groups were balanced with respect to demographic factors such as first-generation status, racial identity and Pell Grant eligibility, a marker of low socioeconomic status.

Students in the VR lab group were 1.7 times more likely to score between 90 percent and 100 percent on their lab assignments than were students in the non-VR lab sections, according to the university’s report. Historically marginalized students also performed better in VR lab sections than in non-VR lab sections. The researchers also considered intersectional identities. For example, a subgroup of women who were members of underrepresented minority groups and Pell eligible earned an average of 84 in the traditional lab section versus 90 in the VR lab section.

“This continues across the board” for other intersectional identities with which the institution seeks to boost engagement and achievement, Hale said. “And when we look at this for fall 2022, we are seeing even higher marks.”

But more than one-quarter of the spring 2022 Bio 181 students opted out of the experiment. Those who opted out had significantly lower GPAs than did those who participated. Also, those who opted out were significantly more likely to be Pell eligible. As a result, the study was unable to report on how this marginalized socioeconomic group with disproportionately higher academic needs would have fared in the VR labs. Also, students who withdrew from the VR labs were not included in the study.

Most students in the VR lab preferred the format over the non-VR alternative, based on interviews conducted immediately after removing their headsets, according to Hale. But some researchers warn against putting too much stock in feedback that happens soon after a learning experience.

“It’s not to say we’re not excited” about opportunities for harnessing VR to teach science, said Jeffrey Ward, clinical professor of law and director of the Center on Law and Technology at Duke University. “But before we replace full-scale all educational funding and efforts in a certain direction, it would be nice to know answers to longer-term questions.” Many inclusion efforts focus on the beginning of the pipeline, while problems remain in the middle and at the end of the pipeline, Ward said.

Like Comparing a Paintbrush and an Apple

Controlled educational studies, including those that attempt to isolate a single feature such as the presence or absence of technology, are rarely slam dunks, as Inside Higher Ed has reported in the past. In Arizona State’s case, the researchers acknowledge some factors for which they did not control.

The researchers assessed the designs of the VR lab and the non-VR lab using a Quality Matters rubric that considered eight general standards (such as learning objectives, instructional materials and learner support) and 23 essential standards (such as whether the learning objectives are suited to the level of the course and whether assessments are sequenced and varied). The VR version of the course received a score of 88, and the non-VR version of the course received a score of 49. (A score of 85 is considered passing.) Ideally, the design scores of the two versions under consideration would have been comparable.

“The courses were about as similar as a paintbrush and an apple,” Hale said.

Also, teaching assistants in the VR labs were observed checking in with students, answering their questions and behaving in a friendly and reassuring manner more than twice as often as teaching assistants in the non-VR labs, according to the study. The study also did not indicate whether an attempt was made to control for the quality of instruction, and a difference there could impact the result. For example, instructors who are drawn to teaching with emerging technology may be more innovative or less experienced in the format. Likewise, those who are drawn to traditional teaching environments may have deep expertise in or be bored with the format.

But Arizona State’s experiment was less an effort to design a controlled experiment than it was to address a real problem at hand.

“The business-as-usual class was going to go live no matter what,” Hale said of the course after which nearly half the students left the major or university. “It’s a little uncomfortable because these are our colleagues … It’s a bit of an indictment about the way things have been done previously. That landed hard for some at ASU.”

The Je Ne Sais Quoi of Real Biology Labs

Virtual reality may offer students unparalleled experiences in biology, such as the opportunity to explore protein structures or to interact with extinct animals. But the technology also has shortcomings, according to some academics. For example, cinematic experiences may reproduce possibly biased narratives in an immersive format that becomes students’ go-to representation of events.

Also, emerging biologists must, at some point, wrestle with moral questions related to research that involves pieces of animals or whole animals, according to several researchers with whom Inside Higher Ed spoke.

“To do biology, often a lot of animals have to die,” Evans of UMass Lowell said. “It’s not clear to me that we want to actually take that away from students.”

To be clear, Arizona State offers traditional labs in biology courses beyond its introductory course. Since the study is in an early phase, the university does not yet have long-term data concerning attrition rates or outcomes when students trained in early VR labs are expected to work in real labs. All outside experts consulted for this story argued that, even in the presence of new technologies, traditional labs play an important role in training emerging scientists.

“Sometimes the chatter that happens on the sidelines with the professor and their peers is every bit as important” as the lab activity itself, McCauley, of UC Santa Barbara, said. Such conversation may spark students’ thinking about their personal scientific trajectories. Also, the real world may ground them more viscerally in human concerns and ethical obligations.

“When you’re in a lab with others and working in a community that’s not intermediated by technology, human values are present,” Ward said.

But some argue that VR need not preclude such chatter.

“It’s a dance between what’s inside and outside of VR,” Vanden Brooks said. During the semester, lab students cycle through sessions in which they spend 15 minutes in the VR and three hours outside the VR. “That’s where all of the chatter happens.” Such a model, Brooks argues, better replicates how biologists work in the real world, as many gather data on their own, after which they might gather to discuss, analyze and craft hypotheses based on them.

Also, not all side conversations are productive. When the Arizona State researchers observed students in the non-VR lab course, students in the lab engaged in side conversations about music, what they did over the weekend or the dating scene, Hale said. Some were disengaged and looking at Facebook.

VR may be impressive to experience, but so is real life, others are quick to note. McCauley is the kind of professor who compels his students to get up out of bed before the sun rises to hear morning bird choruses, smell good and bad smells wafting up wetlands, and even relish moments stepping on (real) cow pies. He advocates for layering augmented and virtual reality tools on top of field experiences.

“You can’t in any kind of accurate way represent those things that haven’t been discovered or things that are changing in ways that we can’t necessarily predict,” McCauley said. “Nature is a moving target in an ever-changing world.”

Ethical Concerns and Opportunities

In an era in which data are a form of currency, some worry when colleges show too much deference to for-profit ed-tech companies.

“There is a slew of for-profit VR companies preying upon the educational world right now,” Ward said. “What protections are there for students about [tracking] eye movements, about brain data, about feedback? If this were driven by educational institutions, I’d have a lot more trust that those protections are in in place.”

But technology also offers opportunities to foster diversity, equity and inclusion. Some students who opt out of dissection labs on moral grounds can have a less diminished experience with next-generation digital tools for learning about anatomy.

“We respect the decisions our students make about how they engage with these labs in class,” McCauley said. “Our use and dependency on [traditional] labs has evolved a lot over the years.”

Also, students with disabilities may benefit from virtual reality labs that offer greater access to more meaningful or robust experiences, and the technology could help curb the urban-rural educational access divide, Ward said.

“I start with optimism” while also remaining cognizant of concerns, Ward said.

For now, all introductory biology students at Arizona State have traded real pipettes for VR goggles. Hale acknowledged that some faculty members at the university were “disgruntled” about the decision to adopt the VR lab in all Bio 181 classes.

“They wanted students to dissect a [real] beetroot,” Hale said. “It’s an experiment … Give me a few more semesters until we get students that are in their junior year, and who knows what we’ll find? Will they be better prepared? Will they be at a disadvantage? What will those faculty think?”