You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

A federal judge ruled Tuesday that Harvard University's admissions policies do not discriminate against Asian American applicants.

The ruling by Judge Allison Burroughs of the U.S. District Court in Massachusetts came in a much-watched case brought by a long-standing critic of affirmative action on behalf of a group of Asian American plaintiffs.

Her decision upholding the Ivy League university's policies confounded the predictions of many commentators, who had seen Harvard's approach as vulnerable.

While she said Harvard's admissions approach was "not perfect," "the court will not dismantle a very fine admissions program that passes constitutional muster, solely because it could do better."

"For purposes of this case, at least for now, ensuring diversity at Harvard relies, in part, on race conscious admissions," Burroughs wrote in her conclusion. "Harvard’s admission program passes constitutional muster in that it satisfies the dictates of strict scrutiny. The students who are admitted to Harvard and choose to attend will live and learn surrounded by all sorts of people, with all sorts of experiences, beliefs and talents. They will have the opportunity to know and understand one another beyond race, as whole individuals with unique histories and experiences.

"It is this, at Harvard and elsewhere that will move us, one day, to the point where we see that race is a fact, but not the defining fact and not the fact that tells us what is important, but we are not there yet. Until we are, race conscious admissions programs that survive strict scrutiny will have an important place in society and help ensure that colleges and universities can offer a diverse atmosphere that fosters learning, improves scholarship, and encourages mutual respect and understanding."

One theme of the judge's decision was that Asian Americans may have a slightly more difficult road, on average, than others. But she said this does not prove discrimination.

Judge Burroughs's decision found that Asian Americans are admitted at a lower rate than white students -- 5 to 6 percent of Asian American applicants were admitted from 2014 to 2017 compared to 7 to 8 percent of white applicants. She also acknowledged that Asian American applicants "would likely be admitted at a higher rate than white applicants if admissions decisions were made based solely on academic and extracurricular ratings."

Burroughs noted that Asian Americans tend to receive worse teacher and guidance counselor recommendations than white students. And Asian Americans are less likely than white applicants to receive athletic recommendations.

"The disparity in personal ratings" between Asian Americans and other groups "suggests that at least some admissions officers might have subconsciously provided tips in the personal rating, particularly to African American and Hispanic applicants to create an alignment between the profile ratings and the race-conscious overall ratings that they were assigning. It's also possible, although unsupported by any direct evidence before the court, that part of the statistical disparity resulted from admissions officers' implicit biases that disadvantaged Asian American applicants in the personal rating relative to white applicants, but advantaged Asian American over whites in the academic rating," Burroughs wrote.

Taken as a whole, "Harvard does not have any racial quotas," Burroughs wrote. "Harvard evaluates that likely racial composition of its class and provides tips to applicants to help it achieve a diverse class. Those tips as necessary to achieve a diverse class given the relative paucity of minority applicants that would be admitted without such a tip." (Here the reference to minority applicants is not to Asian Americans.)

Further, she said, "Harvard's current admissions policy does not result in under-qualified students being admitted in the name of diversity -- rather, the tip given for race impacts who among the highly-qualified students in the applicant pool will be selected for admission to a class that is too small to accommodate more than a small percentage of those qualified for admission."

Burroughs cited various Supreme Court rulings -- which the plaintiffs in the case would like to reverse -- to support her findings.

The Reaction

The immediate reaction to the decision was predictable.

Lawrence S. Bacow, Harvard's president, sent a message to Harvard students and faculty members that said in part, "Diversity of all kinds creates remarkable opportunities and complex challenges. If we hope to make the world better, we must both pursue those opportunities and confront those challenges, motivated always by humility, generosity and openness. The power of American higher education stems from a devotion to learning from our differences. Affirming that promise will make our colleges, and our society, stronger still."

A coalition of Harvard student groups who back the decision issued a statement that said, "Today, the court stopped a blatant attack on diversity at Harvard and at colleges across the country. The court’s decision recognizes that students are more than mere statistics and credentials: they are real people with experiences often inextricably linked to their race. As the court affirmed today, race-conscious admissions is a vital mechanism for creating classrooms that reflect the rich diversity of our country. Students of all races benefit from exposure to people from different backgrounds and a broader understanding of the world we all inhabit. This decision ensures that Harvard students will continue to receive the highest quality education that exposes them to different perspectives and prepares them to be our nation’s future leaders.”

Edward Blum, the president of Students for Fair Admissions, which sued Harvard, said, “Students for Fair Admissions is disappointed that the court has upheld Harvard’s discriminatory admissions policies. We believe that the documents, emails, data analysis and depositions SFFA presented at trial compellingly revealed Harvard’s systematic discrimination against Asian-American applicants.”

Blum added, "SFFA will appeal this decision to the First Court of Appeals and, if necessary, to the U.S. Supreme Court."

The Supreme Court, with the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy, lacks a majority of justices with a record of supporting the right of colleges to consider race and ethnicity in admissions. Meanwhile, another lawsuit challenging affirmative action is getting started -- this one against the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (A federal judge recently rejected requests from both sides in the case that a ruling take place without a trial.)

The Asian American Coalition for Education said, "Such a retrogressive decision discounts overwhelming evidence documenting the school’s egregious anti-Asian discrimination in its college admissions process, and showcases the court’s biased alliance with the defendant on a basis of political correctness and elitist arrogance."

Most higher education associations strongly backed Harvard.

Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education, issued a statement that said in part, “Today’s ruling is especially gratifying because it occurs against a backdrop of continuing attacks on what remains the settled law of the land in this area. As the amicus brief filed by ACE and 36 other higher education groups opposing the challenge to the ‘Harvard model’ of holistic admissions review noted: ‘this lawsuit is nothing more than the first step in a backdoor attempt to achieve the sweeping relief sought -- and denied -- in Fisher II: the end of the consideration of race in college admissions and the restriction of a university’s ability to assemble a diverse student body.’” (Fisher II refers to one of the Supreme Court decisions upholding affirmative action.)

The Closing Arguments

The case wrapped up in February, when lawyers for both sides submitted briefs to Burroughs.

At that time, Burroughs gave hints at where weaknesses might exist in the arguments of the plaintiffs and of Harvard.

“They have a no-victim problem,” Burroughs said, referring to the failure of Students for Fair Admissions to introduce direct testimony from a rejected Asian American Harvard applicant who could point to Harvard's admissions policies as discriminatory. But Judge Burroughs told Harvard, "You have a personal rating problem," referring to the part of the admissions process where personal qualities are considered, and where the odds of Asian American applicants with stellar academic qualifications fell, according to data presented at the trial.

On the issue of an Asian American witness, the issue raised by Judge Burroughs points to a difference between this case and others that have challenged the right of colleges to consider race in admissions. From Allan Bakke, who was rejected by the medical school at the University of California, Davis, to Abigail Fisher, who was rejected for admission as an undergraduate at the University of Texas at Austin, these cases have been based on individuals who claimed that they were rejected because of their race, and their stories were a key part of the evidence. Bakke and Fisher are white.

Students for Fair Admissions says it is suing on behalf of many Asian American students, but there has been much less focus on (and no testimony from) an individual who was rejected. It is unclear how crucial an issue this will be, but Harvard's lawyers have said from the start that they do not believe there is a basis for the Asian Americans to sue.

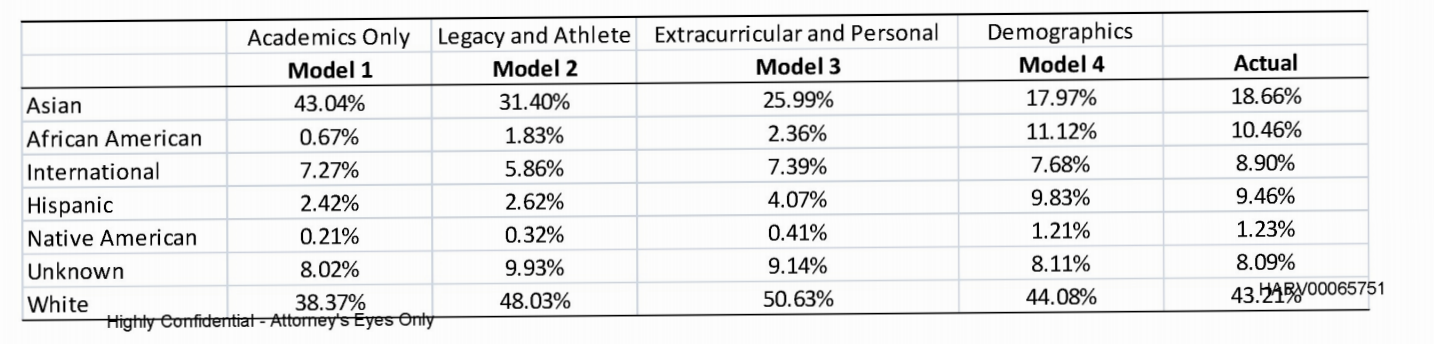

The personal ratings issue is one that has resulted in widespread criticism of Harvard -- even from some who are supportive of the right to consider race and ethnicity in admissions. The plaintiffs -- after years of court fights -- obtained documents from Harvard that modeled various considerations in the admissions process. Harvard says that the table below is flawed and inaccurate, even if the data come from the university.

But it shows how in a given year, various factors in admissions would have produced different shares of the freshman class. Consideration based on academics alone would have yielded a class with more Asian American students than from any other group. But when other factors (such as status as an alumni child or athlete), then a personal rating, and finally consideration of race and ethnicity are factored in, the share of Asian American slots goes down dramatically.

In its closing arguments, Harvard said that this analysis looks bad only based on a false assumption: that the key factors in admissions should always be academic. This might be true at a college where the applicants included many who could not do the work to succeed, the university argued. But at Harvard, the vast majority of applicants could not only succeed but could thrive at the university -- with high school backgrounds that would earn them admission to the vast majority of colleges and universities. In this environment, nonacademic factors may well be decisive, but that is just because there is so little difference (in pure academics) among many applicants.

"SFFA argues that race must affect the personal rating because 'African Americans and Hispanics in the top four academic index deciles have a substantially higher probability of receiving a personal rating of 1 or 2 than whites and Asian Americans,' and because the distribution of the personal rating by race and academic decile resembles that of the preliminary overall rating (which does consider race as one among many factors)," Harvard's final argument said.

"That argument reflects SFFA’s fundamental failure to acknowledge that Harvard’s admissions process is driven largely by nonacademic factors, as well as by academic factors that go well beyond the two components measured in the Academic Index. Comparing applicants’ ratings and admissions outcomes within a given decile of the Academic Index is in effect like running a regression that controls only for GPA and SAT scores; it compares applicants who are similar on those two factors but who may vary in many other ways for which the analysis does not account … But although grades and test scores are certainly important to the admissions process, excellence on those measures is more abundant in the applicant pool than almost any other measure, and even when academic strength is more broadly defined, it is more abundant than other dimensions of applicant strength."

Students for Fair Admissions zeroed in on the personal rating issue in its final brief for the court. It argued that the large shifts in the ethnic and racial makeup of the admitted class once the personal factors come into play can't be explained by anything but illegal discrimination.

"The court therefore must answer a question of great importance to the parties and Asian Americans across the country," the brief says. "Why? Why does being Asian American systematically lead to a lower rating of an applicant’s personal qualities? SFFA’s answer is that Harvard engages in racial stereotyping, a form of intentional discrimination, and that the record contains extensive statistical and other circumstantial evidence to substantiate that charge.

"Harvard’s answer (to the extent it even offers one) is that Asian American applicants simply deserve it -- they deserve lower personal ratings. According to Harvard, Asian Americans applicants -- as a group, year after year -- compare unfavorably to their African American, Hispanic and white peers … Harvard has imposed a statistically significant penalty on Asian Americans. Unless the court is willing to find that the clear racial hierarchy of the personal rating is just a coincidence, SFFA must prevail."

Supreme Court Rulings on Race in Admissions

If the Harvard case reaches the Supreme Court, it could result in the sixth Supreme Court decision on the consideration of race in admissions. The Harvard case would be the first time that such a case involved a private college.

If the Harvard case reaches the Supreme Court, it could result in the sixth Supreme Court decision on the consideration of race in admissions. The Harvard case would be the first time that such a case involved a private college.

- 1978: In Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, the court ruled that the medical school at the University of California, Davis, could not reserve some slots with separate admissions standards for minority applicants. But the court also ruled that colleges could consider race and ethnicity in admissions decisions in ways that did not create quotas.

- 2003: In Gratz v. Bollinger, the court ruled that the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor had unconstitutionally used an undergraduate admissions system in which underrepresented minority applicants received points on the basis of their ethnic or racial background.

- 2003: In Grutter v. Bollinger, the court ruled that the University of Michigan's law school was within its constitutional rights in considering applicants' race and ethnicity because it did so through a “holistic” review and not by simply awarding points based on race and ethnicity.

- 2013: In Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, the court ruled that lower courts needed to apply “strict scrutiny” and not give colleges deference in reviews of challenges to the consideration of race and ethnicity in admissions decisions.

- 2016: In another round of Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, like the 2013 ruling involving the same rejected student, the Supreme Court again upheld the University of Texas's policies, while also saying that the university had “a continuing obligation” of “periodically reassessing the admission program’s constitutionality, and efficacy, in light of the school’s experience and the data it has gathered since adopting its admissions plan, and by tailoring its approach to ensure that race plays no greater role than is necessary to meet its compelling interests.”