You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istockphoto.com/erhui1979

As of today, I am officially an assistant professor at the University of Southern California Rossier School of Education. My transition to the faculty was gradual. I was capable of doing the work in August 2016, after I defended my dissertation. I began doing the work as a postdoc through 2017 and the first half of 2018. Yet now is when all the paperwork aligns with who I am professionally.

Formal distinctions matter, because often it is only such distinctions that signal to those around us that we people of color belong in the academy. It shouldn’t be this way, but it is. As I join the ranks of academe, I feel it necessary to reflect on what it means to belong to a community where I do not often see my identity reflected in my peers.

I hold that sometimes belonging matters, and sometimes it doesn’t. Regardless, belonging to our respective scholarly communities comes with costs that the people within and outside them should recognize. I share my experiences -- and my interpretations of those experiences -- so that others can reflect on their own journey and that of their peers.

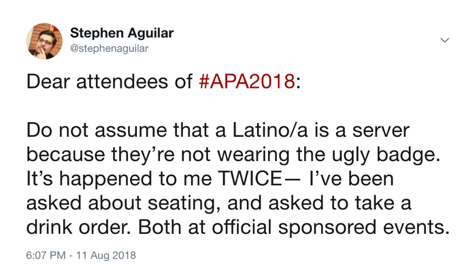

But first, an anecdote best captured by this tweet:

I wrote that tweet during the American Psychological Association’s annual conference in San Francisco after being frustrated by two events. Both signaled to me that some members of the association were unaccustomed to seeing people who looked like me at the conference; their actions signaled that they did not believe me to be one of their own.

My Belonging Questioned

The first instance when my belonging was questioned was at a division-sponsored cocktail reception. As I walked into a sparsely populated venue, I introduced myself to the first person I saw. The conversation, as best I can remember it, went as follows:

“Hi, my name is Stephen.”

“Hi, I’m [redacted].”

“Nice to meet you. Where are you coming from? I’m coming from USC.”

“Oh, I thought you were a waiter and were going to take our drink order!”

Not 24 hours later, I was again mistaken for restaurant staff. That time, however, it was as I was leaving another event. The exchange went something like this:

“Excuse me, is it OK to sit here? Is the bar open seating?”

“I don’t know.”

“Oh, don’t you work here?”

“No. I don’t.”

[awkward pause]

“Oh … well, I asked because, well … you just look so nice.”

“Mm-hmm.”

Let me pause here and acknowledge that, in general, academics are incredibly socially awkward. Social hours held at conferences might as well be case studies in horrible introductions and stilted conversations. That said, the exchanges above signaled to me, above all else, that I was not immediately seen as a member of what I have come to view as my scholarly community. This is obviously hurtful. Unfortunately, I am beginning to realize that it comes with the territory.

You may be wondering what I was wearing. Rest assured that I was dressed professionally and did not have on anything that should have remotely signaled to anyone that I worked for a restaurant. Know that if you wondered what I was wearing that you are, in fact, a part of the problem.

Reflecting on Belonging

Although my sense of belonging is an internal process, much of what makes it manifest begins as cues that I receive from others. If others question my belonging, I cannot help but question it myself. Both of the aforementioned events made me wonder what it means to be part of a community that does not readily recognize me as one of its own.

I conclude that, as a first-generation scholar of color, I cannot ever truly feel an unadulterated sense of belonging due to the fact that academe has a history of exclusion -- and is actually predicated as much on exclusion as on anything else. We scholars of color often make inroads in hopes that those behind us will find it easier. The reality, however, is that we cannot blaze a trail without attending to the boundaries that re-emerge behind us once we’ve succeeded.

When belonging matters. If you are seen as someone who does not belong, you will not get a job, nor will you get tenure. Belonging matters because it is intertwined with your chosen profession, your progression within that profession and your livelihood.

The best description I have heard about academe is that it is tribal. Each discipline, subdiscipline and cohesive scholarly community has customs that define it and its method of inquiry. It is imperative for all emerging scholars to understand those customs and to learn how they are enacted. This is especially important for scholars of color, whose membership in a given community may be more readily questioned.

Often, enacting any given custom will feel like wearing a costume or playing a part. That is normal. If you are a person of color earing a Ph.D., or one with a Ph.D. in hand, chances are you are well accustomed to donning the costume of your field and playing a role.

Any given role has characteristics, mannerisms and language that you must learn. Just as every part that an actor/actress plays is the product of their own personality and the demands of the role, so too is your part in your community the product of who you need to be seen as and who you are when you are alone. The trick is to preserve enough of yourself in that role so that you begin to shape your community in a way that enables others like you to be more readily seen as members. This is an unavoidable burden that every scholar of color must bear. Rather than avoid it, we should acknowledge it and work toward shaping our chosen scholarly communities.

When it doesn’t. There are limits, however. I urge other underrepresented scholars in similar positions not to spend an inordinate amount of time pondering over whether they belong in the academy or not. I’ve spent enough time doing that for all of us. If you take too much time to reflect on whether or not you belong, you may be slowed down. Work toward making your presence a fixture -- a given.

The key, I think, is to find balance. You should not strive to belong if it makes your life, or the lives of others, considerably more difficult. As I mentioned before, depending on your personal history, feeling a pure sense of belonging might not be attainable. Seeking to belong under those circumstances, then, might lead to making compromises that will affect your well-being. Relatedly, there is a difference between finding a happy nexus between your own identity and what your scholarly community asks of you, on the one hand, and assimilating to the point of contributing to exclusionary behavior on the other. Focus on the former and avoid the latter. Find what works for you, and do not apologize for it.

Regardless, I believe that all of us who are members of underrepresented communities should try to make it easier for those that come behind us. What that means will differ depending on the customs of your scholarly community. A good rule of thumb, however, is to identify parts of your experience that were difficult and can be changed, and then to try to change them.

What it costs. The cost of being a member of an underrepresented community in a faculty position is isolation. “Upward mobility,” I feel, is a misnomer. Any first-generation college student, Ph.D. or faculty member knows (or should know) that our mobility is as lateral as it is upward. We often move away from our homes, from our peers and -- all too often -- from our cultural customs.

For example, I respect that many Americans care about and celebrate Thanksgiving, but it is not, and will never be, a holiday that is important to me because I didn’t grow up celebrating it. Every November, I find that I am both perplexed by the power pumpkin spice has over my peers and saddened that I cannot readily find someone to share my perplexity with. This is a deliberately innocuous example. After all, I get a few days off. Still, one can imagine other customs and norms that occur in the academy that leave scholars of color feeling isolated.

If you happen to be a member of the racial and/or cultural majority and you feel strongly about diversity, I suggest that you conduct a few thought experiments. Imagine being isolated, and sit with any triggered feelings of isolation. Think through what you would or wouldn’t compromise to feel like you belonged to a community where your race/ethnicity/gender are underrepresented. If you always feel like you belong, interrogate why that is.

Experience those feelings, reflect on them and (most importantly) keep them to yourself. It is not necessary for you to share your feelings or insights with an underrepresented peer, because that would be like showing a paper cut to a person with a severed arm in hopes of commiserating. Best to avoid that. Let your actions signal to those around you that you are committed to diversity. Note: that necessitates calling out your peers when they contribute to exclusionary behavior.

Instead, keep any generated feelings or insights as a tool in your interpretive tool box so that whenever you see a Mexican American, African American or other underrepresented person at a conference, you do not automatically assume that they are there to serve you. If you do that much, you may contribute at least in some small measure to your community’s ability to meaningfully integrate a diverse set of scholars.