You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

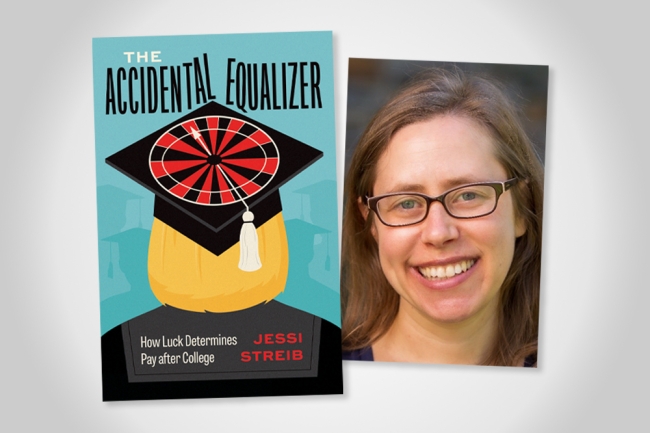

University of Chicago Press

In her new book, The Accidental Equalizer: How Luck Determines Pay After College (University of Chicago Press, 2023), Jessi Streib, a sociologist at Duke University, explores why college graduates tend to earn similar incomes regardless of their class background.

Examining the outcomes and earnings of graduates of one public university’s business school, Streib finds that employers are driving the trend. Within the midtier labor market she investigated, employers are so opaque in their hiring practices and starting salaries that students from advantaged backgrounds are unable to use their resources and connections to gain a leg up. Furthermore, hiring managers for entry-level positions vary greatly in the skills and experiences they value, making it impossible for an applicant to leverage privilege in an interview.

Based on hundreds of interviews with business school graduates and the employers that subsequently hired them, Streib’s book ultimately argues that college is not, in itself, the great equalizer; the impossible-to-navigate job market is. She spoke by phone with Inside Higher Ed about how her research could impact the way students, universities and businesses approach the job-search process. Excerpts of the conversation follow, edited for length and clarity.

Q: Most people, I would assume, aren’t really aware of what you refer to as the “luckocracy” and believe that something else drives young people’s employment after college. What made you want to look into the idea that, actually, luck is the real driving factor?

A: I think most people’s perception would be that students from more advantaged class backgrounds would graduate from college and earn more than students from disadvantaged class backgrounds. And that’s because, when we think about the things you need to get a high-paying job, students from more advantaged class backgrounds have more of them: connections to professionals, status symbols, higher GPAs and more internships. I think all of those are like, “Oh, if you really want to get this great, high-paying job, intern, intern, intern and network, network, network.” And it turns out that those inequalities are very real, they exist, but when students graduate from the same college, at least, they go on to earn the same amount on average, regardless of their class background. My study was trying to figure out, how can that be? How can all of these inequalities in the things that we know help you get a job not translate into inequalities in pay after college?

That’s where the luckocracy comes in. All of those inequalities exist, but at least some labor markets, including the one I studied, neutralize those class differences, and they do that in two ways. They hide information about where and how to get ahead, and [students are] evaluated on class-neutral criteria. So students from all class backgrounds are going to have to guess where and how to get ahead, and because they’re evaluated by class-neutral criteria, their guesses are going to have an equal chance of paying off.

Q: The lack of transparency, as you just said, is a big contributor to this. A lot of states are making strides to mandate that employers post accurate salary distributions; transparency on the employer’s side is really being pushed in a lot of ways. Do you think that’s going to change things a lot for students entering the workforce, and what might those changes look like?

A: I think it depends on how it’s done. If pay transparency means I’m going to give you a pay range that is so big, that it’s from X to two times X, I don’t think that’s going to change anything. If pay transparency is a pretty exact number, then it really could. I think it’s a weird thing to say, and it’s kind of this uncomfortable trade-off, that if we have pay transparency, that means everybody can know where the highest-paying jobs are, and that means that the people with the most resources are going to be able to leverage them to get those jobs.

Q: Do you think there’s a way that those two things can be reconciled so that pay transparency has the positive effects that it’s intended to have? Or under the current systems that we have in place, is that really kind of impossible?

A: I don’t want to say it’s impossible. If employers took a lot of additional steps, potentially, you could have pay transparency and have equal access to those jobs for students in different classes. But I think that’s going to be hard to enforce. Let’s say we know that company X pays a lot more than company Y. Well, who has better connections to company X? Chances are it’s students from more advantaged backgrounds. So, they’re going to be able to use those connections to get the job more [often], or just to find out, “Oh, they’re looking for people with this particular skill,” and then to be able to produce that skill.

It’s hard to imagine, if we all knew where the highest-paying jobs were, that the students from advantaged class backgrounds wouldn’t figure out a way to get them. Right now, I think one of the really surprising things to people would be that even though students from more advantaged class backgrounds have a lot more connections, those connections aren’t as helpful as they would think. Because, although they help them get jobs, those jobs aren’t necessarily high paying, because their connections also don’t know what they pay. Once you let their connections know what they pay, and let [students] know what they pay, I think we’d end up with a system that looks a lot more like American colleges, where the higher-paying, the more prestigious [the workplace], the more we’d see class inequality, with the more advantaged getting that higher-paid position.

Q: Should colleges make an effort to emphasize the luck involved or the fact that students might need to be prepared for a very different experience at interview A versus interview B?

A: I think knowing that it’s a bit unpredictable is a good thing to know. That can help students feel like even if they don’t know what’s coming, they know they don’t know.

The luck thing is a trade-off. On one hand, I think if they know luck matters, it’s helpful in the sense that you don’t take things so personally, whether it’s going really poorly or it’s going really well. You don’t take pride that’s unearned and shame that’s not, if it’s not going well. You kind of know, if you keep trying, chances are you’ll be on the receiving end of luck at some point.

The downside, though, is, if you know it’s luck, you might feel a little bit disempowered and feel like, “Well, why should I invest in all these skills when who knows what skill they’ll ask me about anyways? And who knows how they’ll evaluate me, so why do a lot to prepare for that?”

If you do want people who are more prepared, telling people that a lot of it is luck might not do a lot to prepare them or incentivize that.

Q: Bearing this in mind, what are the reasons for students to want to invest in their skills? Knowing that having five internships versus one internship will most likely get them similar income outcomes, do you think students should still be trying to get those opportunities, whether for their career further down the line or just their personal enrichment?

A: I think it’s hard to know and depends on what you want. It might not pay off in earnings, but maybe it just makes you feel more confident or better prepared. If that’s what you want, then great. It might also give you a chance to see different companies and how they work, and that might be helpful when you’re trying to figure out what kind of job you want in the long term, especially if you’re able to do different positions. So, I think there are reasons to do the internships that are not about getting higher pay. That said, if you want to just have a really fun summer, I think the findings kind of support that that’s not the end of the world; you don’t have to focus your whole life [on] how to get a job and that can be OK.

Q: This book, in some ways, seems to support the argument against colleges’ worth; in one part you mention that some of these jobs could just as easily be done without a college degree. What are your overall thoughts on the argument that college is not worth the cost, and how does that argument apply specifically to those working in the midtier business labor market group you investigated for this book?

A: For a lot of the jobs that the students end up doing, they could have easily done them out of high school. If employers were willing to hire [the business school graduates] at that point without a college degree, they wouldn’t have done [their jobs] any worse than they do them four years later. So, in that sense, they don’t need the degree. In the other sense, a lot of these jobs you can’t get without a college degree, so, as long as that’s true, then they do need to go. I don’t want to make an overall statement about colleges being worthwhile or colleges not being worthwhile, but I will say to do some of the jobs that they end up doing, they don’t need a college degree.

Q: Do you think that the support of career centers makes college more worthwhile? For students going into the midtier business labor market, is that one of the most important elements of college ?

A: I think some students feel that way. It’s really tangible advice. A lot of the students I would talk to would say, “I can’t believe my friends in the humanities don’t know how to write a résumé. I really know, and college has really helped me with that.” They feel that. Could they have spent an hour online reading about what makes a good résumé and then found somebody to show it to and gotten some feedback? Probably. I think it makes them more confident; I think it makes them less likely to make some mistakes, so maybe they get jobs faster. But I don’t know; I guess I would like college to be more than about the kind of minute details of how to write your résumé and how to do an interview and more about the skills that are needed for doing good work or being a good person.