You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

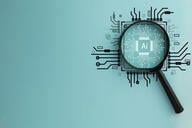

Percentage of students with advisers who listened, respected and cared

NSSE, Indiana University

What makes for successful advising? Listening, respect and caring, according to new data from the National Survey of Student Engagement, which Indiana University’s School of Education Center for Postsecondary Research administers annually.

“A trusting and respectful rapport with an advisor is essential for new students adjusting to and navigating a complex institution and for seniors looking to maximize opportunities within their major,” researchers wrote of data gleaned from the 2020 survey’s module on academic advising. “Among the primary traits possessed by advisors who develop positive relationships with students are active listening, empathy and cultural sensitivity.”

The LRCs

Some 57,000 first-year students and 58,000 seniors from 217 bachelor’s degree-granting institutions in the U.S. and Canada participated in the NSSE Academic Advising Topical Module in the spring. Topics were adjusted from the NACADA academic advising core competencies model, which frames advising as work that is at once conceptual, informational and relational.

While each advising competency matters in and of itself, researchers at Indiana observed that how students rated their advisers’ relational skills -- specifically their listening, respect and caring, or the “LRCs” -- strongly correlated with their other competencies.

In other words, advisers who are good at making students feel cared for and understood are probably good at making time for them and guiding important academic and career decisions, too.

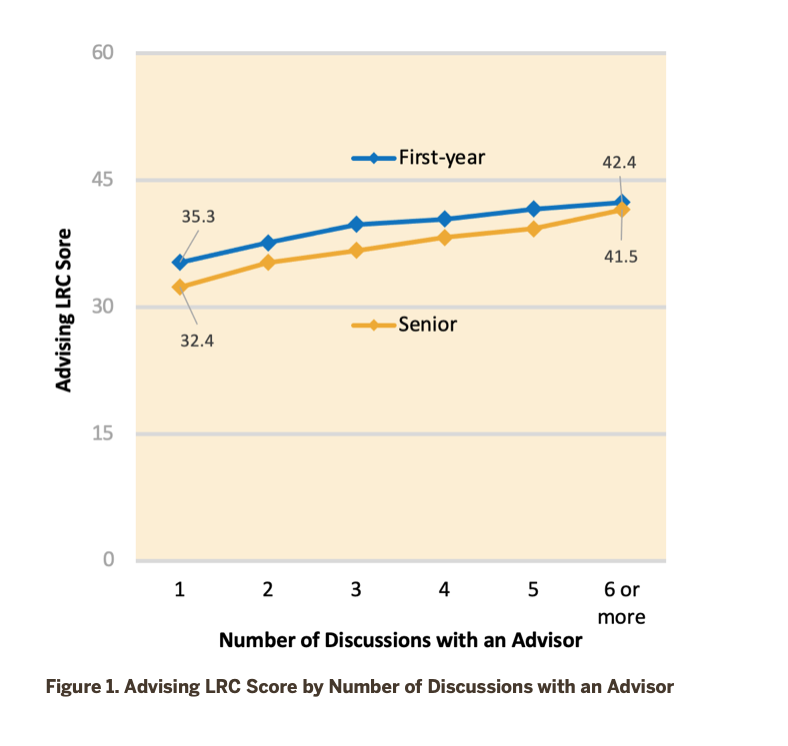

Advising LRC is positively linked with the number of advising discussions had between a student and their adviser, for instance. Nearly all students surveyed discussed their coursework and interests with their adviser once per year, but students in both years studied -- first and senior -- show a positive association between higher LRC and more frequent discussions.

Eric R. White, executive director of the division of undergraduate studies and associate dean for advising, emeritus, at Pennsylvania State University, who was not involved in the study, said the results didn’t surprise him.

“Of course, all advisers should listen, be respectful and caring,” he said. “This is a given and any advising supervisor who finds advisers who do not exhibit these traits probably shouldn't be advisers in the first place.”

Notes for Faculty Advisers

A note to faculty members: the study asked students more about the advising they were getting than who was doing the advising. So both part- and full-time faculty members, along with professional, full-time advisers and career counselors are considered advisers and may drew lessons from the data.

Students' open-ended responses demonstrate variety in how students connect with and sometimes find their own advisers. “A professor that was not assigned as my academic adviser was most helpful to me because I was able to build a relationship with the professor and I felt she was the most invested in my overall well-being,” wrote one senior agriculture major.

Wrote another senior majoring in sociology: “My faculty advisor has been the most helpful by guiding me academically in my research interests, professionally in potential career avenues, and personally by genuinely caring about my well-being and growth in life.”

And this, from a first-year student studying chemistry: “My primary advisor has been the most helpful; he is always kind, respectful, and considerate when I interact with him, and that is incredibly helpful for me.”

Jillian Kinzie, a senior scholar at the NSSE Institute at Indiana, said advising programs and how advising is delivered differs from place to place. Several colleges and universities highlighted by the institute this year all rely on a mix of professional and faculty advisers, while one has career coaches, she said.

The common link between them is the LRCs, or what Kinzie called the “tenets of advising practice.”

“They represent the interpersonal attentiveness of advisers,” she said.

Pandemic Pressures

For these reasons and more, Kinzie said the findings have implications not just for advising but for teaching and learning. Those include encouraging more instructors to “ask how students are doing, to reach out to suggest advising resources to help students maneuver through academic policy challenges that have surfaced during the pandemic,” such as some “ridiculous ones” about seat time, residency requirements and more.

Most students completed the survey last spring but before March and its COVID-19-related disruptions. But students’ early responses and later, post-pandemic ones are similar, Kinzie said.

At the same time, remote instruction “forced changes” to the advising practice, she said, in many ways putting greater demands on faculty members.

The switch to all- or more remote instruction means students need more help with technological shifts and navigating hazier advising structures. These are labor-intensive demands but relatively clear cut. Much more complicated is the trauma-aware teaching and advising that many experts say students have needed for months now, amid public health, financial, racial, political and personal crises.

Kinzie said that professional and faculty advisers alike “have become more aware of this issue and are reaching out to help students who may need mental health counseling to seek care or at least check in with all students more frequently.” Again, she said, “active listening and outreach in the form of ‘How are you?’ is recommended.”

Now more than ever, she continued, students may need to be “listened to and cared for.”

According to the survey data, this happens for most students. Yet about 38 percent of first-years still indicate that advisers only actively listen “some” or “little” to their concerns.

Diversity

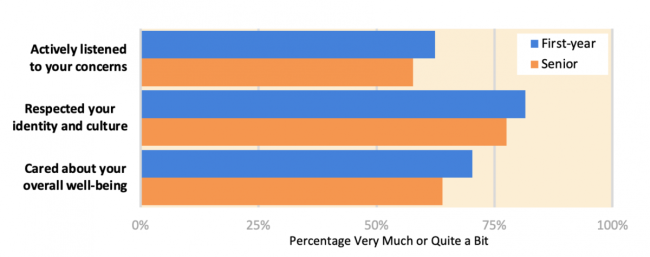

On the “respected your identity and culture” question, students who experienced “very little” or “some” respect ranged from 30 percent among American Indians or Alaska Natives to 16 percent among white respondents, Kinzie said.

“Given the weight on many students right now, this is leaving too many students not actively listened to and respected.”

Underscoring her point, Kinzie said that for students doing coursework online because of the pandemic, “their only connection to the institution may be faculty and advisers. It’s important that those interactions are interpersonally sensitive and caring.”

Cross-checking personal attentiveness with a student’s race, the researchers found differences to be relatively small. Even so, they say, "Such differences are worth exploring if even small effects are related to real benefits or consequences for some groups of students. Advising leaders are encouraged to consider how their day to day policies and practices affect diverse students differently."

Cross-checking personal attentiveness with a student’s race, the researchers found differences to be relatively small. Even so, they say, "Such differences are worth exploring if even small effects are related to real benefits or consequences for some groups of students. Advising leaders are encouraged to consider how their day to day policies and practices affect diverse students differently."

Kinzie said that with respect to “social justice unrest, it’s perhaps never been more important to respect culture and identity. White students have the privilege of not having to think much about this. But we see POC students experience this less.”

The team behind the survey says advisers can make it routine practice to ask students if there are places within the institution or campus environment where they feel “comfortable being themselves and how they are connected in the campus community.”

Retention

First-year student retention is another, ever-critical area of focus that has only gotten more challenging with the pandemic. In the institute’s 2020 survey, most first-year students asked toward the end of the academic year about returning to their institutions for a second year said they would.

Crucially, though, the students who intended to return had higher advising LRC scores or ratings than those peers who said they wouldn’t return.

“Overall, the amount of listening, respecting and caring experienced by those who intend to return is significantly higher than those who responded ‘not sure’ or ‘no’ (do not intend to return),” the report says. “These results suggest institutions should investigate their student advising experiences closely to further understand their specific persistence factors.”

By student group, first-year students with a nonbinary gender identity were less likely to intend to return -- and those who said they were leaving had lower LRC scores than their persisting peers.

Those who did intend to return experienced “advisors who listen, respect, and care on par with the experiences of man- and woman-identifying peers,” according to the study. “Again, these results confirm the connections between beneficial advising practices and student success.”

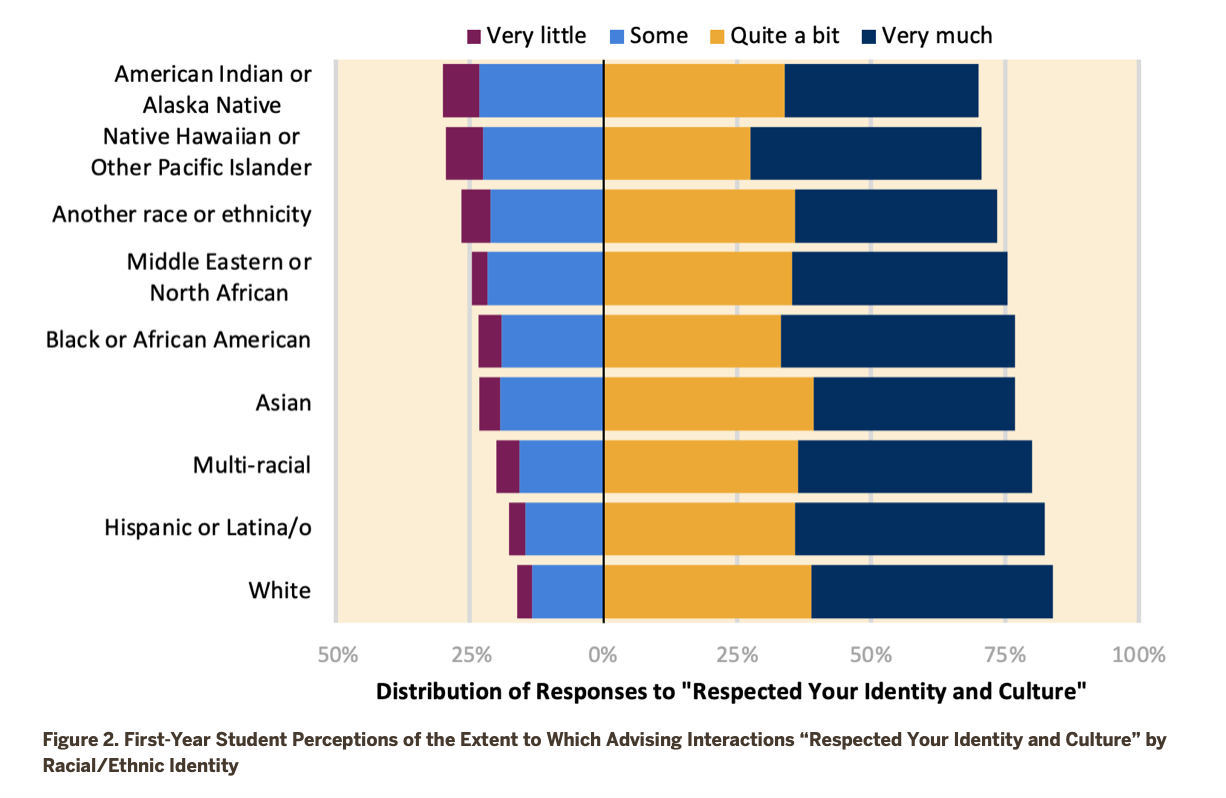

First-year students across all racial groups who intended to return for their second year reported significantly higher LRC than their peers within the same racial identity groups who did not intend to return or weren’t sure.

The institute rated LRC on a scale of zero to 60. For those students intending to return, LRC scores were between 39 and 42, on average. For students who were on the fence or out, LRC mean scores were between 27 and 34.

Seniors were a different story, as their advising had a more narrow focus on their major coursework and career plans. Most seniors said they relied on departmental advisers for academic guidance, and some disciplines performed better than others. Students with majors in the arts and humanities, education, and social service experienced the highest LRC scores with an average score of 40. Engineering students experienced the lowest mean LRC at 37.

Most seniors said their experience at their institutions was "good" or "excellent." But those most likely to say so had significantly higher LRC scores than those who didn’t. They also varied by racial group. On average, students whose advising interactions involved higher levels of LRC expressed a higher sense of belonging.

‘Everyone’s Business’

Kinzie said belonging as a metric and a feeling is “inherently important, but even more so as we are operating in greater isolation.” Findings indicate a clear relationship between belonging and persistence, she added, and “our analysis of students’ experiences with advising demonstrate that the interpersonal aspects of advising interactions contribute meaningfully to sense of belonging.”

White said that over all, “academic advising during this pandemic was able to pivot to an online culture much more easily than, say, instruction or student affairs activities. And that it is to the credit of the profession.”

At the same time, he said, “all of this has come with a cost.” Students face many stressors, and academic advisers are often the "first responders" in academe, “simply because they are the most accessible.”

Some institutions even report students making even more contact with their advisers during remote-only instruction than when there are in-person options, he said. That’s hardly a bad thing, but White said he feared that advisers “and probably the entire higher education endeavor will be so exhausted that the desire to return to how things were will be the natural response.”

That would be an “unfortunate circumstance,” he said, “because now is the time to examine the very nature, purpose and mission of academic advising within higher education.” (White has previously written about what paradigms he believes should change within advising in light of COVID-19 for Inside Higher Ed.)

That would be an “unfortunate circumstance,” he said, “because now is the time to examine the very nature, purpose and mission of academic advising within higher education.” (White has previously written about what paradigms he believes should change within advising in light of COVID-19 for Inside Higher Ed.)

Now is also the time “to think very clearly about the ratios of adviser to advisees,” given the “intensity” of interactions during COVID-19, he said. Similarly, institutions should review the platforms and applications and other technology by which advisers and advisees are connecting.

Indeed, institutions have used previous survey data to inform how they run advising, including adding time to advising appointments to make them more impactful.

White said one big takeaway from 2020 is that the “number of decisions a student has to make has increased significantly.” There are decisions about pass-fail options, how many courses to take and even whether to stay in college -- all of which have potential lifelong implications, he added.

Still, White cautioned leaving too much up to advisers alone and resisted putting too much emphasis on advising and retention data in particular.

“I see retention as everyone's business in higher education, and that when a student chooses to leave a particular institution or move to another school [it] often involves variables that an individual adviser has no control over -- and indeed even the student may have no control over.”