You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

istock.com/Brian A. Jackson

Flexibility stigma is a term scholars use to describe work places that punish those who don’t fit the “ideal worker” profile: solely devoted to one’s job, available 24 hours a day and traditionally male. Lots of studies suggest that in academe, such biases are particularly prevalent in the sciences, and that women with young children are the most frequent targets -- hence the “leaky,” gendered STEM pipeline.

But a new study argues that both men and women with small children report and resent inflexible department cultures. The study also finds that even non-parents resent flexibility stigma, with negative consequences for the department over all.

“Much of the flexibility stigma literature presumes that it is mothers rather than fathers whose parenthood obligations are more likely to trigger stigma,” the study says. “In contrast, we find that flexibility stigma is not just a mother’s problem; mothers and fathers of young children are equally likely to report the presence of flexibility stigma in their departments.”

It continues: “Related, we find that perceived flexibility stigma is negatively related to desires to remain in one’s position, overall satisfaction, and feelings of work-life balance over and above [researchers’ emphasis] gender, family status, and career-relevant variables.”

The study, called “Consequences of Flexibility Stigma Among Academic Scientists and Engineers,” was published in the most recent Work and Occupations journal. (The full study is available to subscribers only, but an abstract is available here.) Lead author Erin Cech, an assistant professor of sociology at Rice University, said she wanted to look at the “mismatch” between outdated, 9-to-5-type expectations for workers and their actual needs, and the consequences of that mismatch. She said that doing so in an academic environment, where workers exhibit devotion to their jobs and scheduling flexibility is relatively high, would be a good place to start.

"We chose to do this study among academics because we thought [flexibility stigma] would be better," Cech said, given that faculty surveyed had relatively low teaching loads (about two courses annually), and 70 percent said that they had "a lot of control" over how they balance their work and personal lives.

"So if we were to find flexibility stigma among workers with a great deal of schedule control, we assumed it would be likely to occur elsewhere," she said.

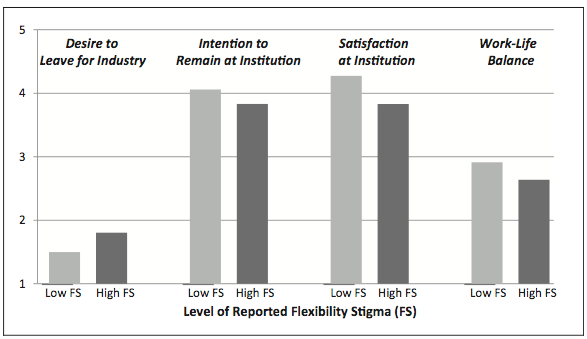

Some 266 STEM faculty members at an unnamed top research institution with "preeminent" science and engineering programs responded to an online questionnaire about family status, gender and perceived levels of flexibility stigma in their departments. They were also asked to rate, from 1 to 5, whether or not they would consider leaving academe for careers in industry, their job satisfaction, and achieved work-life balance. Researchers used advanced statistical analysis to establish relationships between various responses and variables.

Faculty members’ belief that making use of work-life policies, such as taking an occasional sick day to care for an ill child, leads to negative consequences in their departments is strongly related to their beliefs that mothers and fathers are seen in their departments as less committed. Women are more likely than men to report flexibility stigma, and parents with children under age 3 are likelier to report stigma than their non-parent colleagues. And contrary to the researchers' expectations, mothers and fathers are equally likely to report flexibility stigma.

Although 75 percent of the respondents are parents, just 14 percent have taken advantage of work-life policies.

Over all, respondents have a low likelihood of wanting to leave academe for industry and are generally satisfied with their experiences at their institution. But they disagree, on average, that they have work-life balance. And those respondents who report flexibility stigma are significantly more likely to want to leave academe for industry; less likely to want to remain at the university long-term; feel less work-life balance; and are less satisfied with their work over all. That’s controlling for demographics, career and family status -- meaning even non-parents feel the sting of flexibility stigma.

Results were similar across disciplines.

Mary Blair-Loy, the study's co-author and an associate professor of sociology at the University of California at San Diego who is the founding director of the Center for Research on Gender in the Professions, said the results show that the so-called “work devotion schema” that rewards the ideal worker is “wonderful for celebrating professional dedication. But it’s important that we balance it with an awareness that people do have responsibilities outside of work.”

She added: “We shouldn’t be stigmatizing our colleagues during the short period of their lives while they’re also taking care of children.”

Cech also noted that one consequence of flexibility stigma – employee turnover – can be costly. Beyond low morale, Cech said flexibility bias can have financial repercussions for employers. Startup packages for new science and engineering faculty run between $90,000 and $400,000, she said.

The research is part of the National Science Foundation-funded project “Divergent Trajectories: A Longitudinal Study of Organizational and Departmental Factors Leading to Gender and Race Differences in STEM Faculty Advancement, Pay and Persistence.”

Despite some sobering findings, the study notes a possible “silver lining.”

“Many faculty who do not currently have young children at home are nonetheless aware of (and affected by) flexibility stigma in their departmental climates,” it says. “Broader worker awareness of problematic environments for colleagues with child care responsibilities suggests that at least some professionals who are not themselves targets of this stigma might be potential allies in altering this aspect of work place climate.”

Blair-Loy attributed some of the shared dissatisfaction with flexibility stigma among workers, even non-parents, to the collaborative nature of science. One might think that childless scholars get ahead due to their status, she said, “but that’s not how science works.” When one member of a research team struggles, all members struggle, she said.

Cech said departments interested in busting flexibility stigma should "shift the conversation" about making use of family-friendly policies to parents generally -- not just mothers. There’s no “silver bullet, and that’s why we’re still talking about this 20 years down the line,” but departmental leaders openly endorsing the use of such policies could go a long way to advance them, she said.

Nicholas Wolfinger, an associate professor of consumer and family studies at the University of Utah, co-wrote Do Babies Matter? Gender and Family in the Ivory Tower, part of a long-term research project on the impact of family status among faculty. The book addresses flexibility stigma with qualitative data (Cech and Blair-Loy claim they are the first to address flexibility stigma and its consequences with quantitative data about persistence and job satisfaction). Wolfinger said the new study was prone to critique in that it considered only one university. It also is unclear based on the data collected whether flexibility stigma was distinct from “garden-variety prejudice against women."

But Wolfinger said the study was likely to get people talking about an important subject, and agreed that the best way to reduce stigma is to include fathers in conversations about family-friendly policies.

"What we say in the book, and we say this more than once and fairly forcefully, is that the secret to making these policies work is that men have to use them," he said.